INTRODUCTION

Transgender individuals comprise approximately 1 million people in the United States alone.1 Despite recent awareness of the transgender community, risks and disparities remain for this population in their access to health care. Transgender health care costs, recent policy adjustments, and medical education have been reported as primary barriers to receiving adequate health care services.2–4 Current guidelines affirm that hormonal and surgical interventions alleviate gender dysphoria amongst the transgender population.5 However, access to these treatments has been subject to targeted discrimination by insurance companies through increased costs.6 Although federal policies, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, prevent insurance companies from denying health care coverage to trans-identifying patients, state legislation currently attempts to perpetuate cost disparities.7 Cost disparities for hormonal treatments and surgical reconstructive surgeries have deterred transgender individuals from seeking gender-affirming care.2 These limitations incur significant harm to transgender individuals, as rates of suicide and psychological distress (feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness) are amongst the highest in this population.8

Prior data suggest limitations in medical education and biases from physicians prevent transgender patients from equitable access to their required care.9 For example, a 2018 study showed that more than half of Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) -accredited academic practices do not have a comprehensive LGBTQ-competency training program.10 This demonstrated a lack of prioritization for LGBTQ care in medical school curriculums. Inclusion of LGBTQ-specific care in the medical school curriculum should be extended into the overall health care environment because representation of the transgender community is minimal. These controversies identify circumstances for health care providers, policymakers, and educators to optimize transgender patient care. This review attempts to address the temporal disparities in health care costs, policies, and medical education in the treatment of transgender patients in the United States.

METHODS

We performed searches on Ovid MEDLINE between April 15 and May 2, 2021. Single search items, listed alphabetically, included clinical competence; costs and cost analysis; education, transgender persons; estrogen replacement therapy; gender dysphoria; gender identity; guidelines, transgender persons; health policy; health services accessibility; hormone replacement therapy; insurance coverage; insurance, health; medical, continuing; population, transgender persons; sex reassignment surgery; students, medical; transsexualism; and United States. We selected “explore” and included all subheadings for the listed keywords to allow for a more comprehensive search. Combined “AND” terms included the following, listed alphabetically: clinical competence AND transgender persons; costs and cost analysis AND hormone replacement therapy; costs and cost analysis AND sex reassignment surgery; education, medical, continuing AND transgender persons; estrogen replacement therapy OR hormone replacement therapy; gender dysphoria AND transsexualism; guidelines AND transgender persons; health policy and transgender persons and United States; health services accessibility and transgender persons and United States; hormone replacement therapy AND transgender persons; public policy AND transgender persons; and sex reassignment surgery AND transgender persons. Combined “OR” terms include the following, listed alphabetically: costs and cost analysis OR insurance, health; gender dysphoria OR gender identity; transgender persons OR transsexualism. The number of articles that appeared using our original single search item criteria was a total of 1 538 866. To further narrow down the original pool of articles after utilizing “AND” “OR” combined terms, we then limited our search to English language, humans, publication year 2012 to current, and selected articles relevant to only the United States to obtain direct results relevant to our study.

RESULTS

Treatments and Health Care Costs

Transgender individuals present with various signs typically during late adolescence into early adulthood. These signs include gender incongruence, inability to articulate one’s gender identity, and gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria is a psychiatric diagnosis, wherein individuals experience significant discomfort with the lack of congruence between one’s perceived gender identity and gender at birth. Current practice guidelines assert that the cornerstone of treatment for gender-affirming care is initiated by hormonal therapy.11 Gender-affirming surgery is then indicated if a transgender person is refractory to hormonal treatment for a minimum of 1 year.12 However, those necessary treatments come with exorbitant costs and lack of legislative protection.

Hormonal Therapy

Based on the clinical practice guidelines of the Endocrine Society and World Professional Association for Transgender Health, initiation of pubertal blocker therapy using gonadotropin-releasing hormone should be provided for adolescent transgender individuals who experience symptoms of gender dysphoria. Subsequent sex hormone treatment is required for patients who experience persistent gender dysphoria despite pubertal blocker therapy.11 In a cost-effective analysis study by Padula et al,13 the Massachusetts Group Insurance Commission indicated that transition treatments, such as hormone replacement therapy using sex hormones, carry a baseline fixed rate cost of $4350. Health care expenditure related to the provision of hormone replacement therapy is mental health evaluation, which has a base cost of $2175.13 However, in line with the variations in state insurance policies, costs of hormonal treatment may be analyzed based on an individual’s insurance coverage. A study by Koch et al2 found that the cost of hormone therapy for a transgender man without insurance coverage was an estimated $720, with an estimated $11000 for secondary medication costs. For a transgender man with insurance coverage, the estimated cost of hormone therapy was $230, with an estimated secondary medical cost of $4000. For transgender women without health insurance coverage, the estimated cost of hormone therapy was $2370, with $14000.00 in secondary medical costs. In contrast, for transgender women with medical insurance coverage, the cost of hormone therapy was $500, with $5000 in secondary medical costs2 (Table 1). Because the United States is working toward a more inclusive health care system, legislation should be passed to create a standardized system that minimizes the discrepancies in out-of-pocket costs for insured vs uninsured transgender individuals. The differences in costs of care between insured and uninsured individuals further highlight the health care disparities among transgender populations.

Gender-Confirmation Surgery

Gender-confirmation surgery for transgender females includes facial feminization surgery, breast augmentation, orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, chondrolaryngoplasty, and voice surgery. On the other hand, surgical treatment for transgender males includes facial masculinization surgery, subcutaneous mastectomy, and penile reconstruction surgery.14 Data from the Massachusetts Group Insurance Commission revealed that the cost of male-to-female gender-confirmation surgery was estimated at a fixed rate of $17675, but also requires postoperative hormone replacement therapy. The cost of male-to-female confirmation surgery with hormone replacement therapy was estimated at $22025. On the other hand, the cost of female-to-male gender-confirmation surgery alone was estimated at $10308.00, while the estimated cost of combined female-to-male gender-confirmation surgery with hormone replacement therapy was $14658.13 Koch et al2 asserted that the cost of surgical treatment varies based on insurance coverage. The cost of a mastectomy for a transgender man without health insurance coverage was estimated at $7000. For transgender men with insurance coverage, the cost of a mastectomy was estimated at $2000.00. For transgender women without health insurance coverage, the estimated cost of a vaginoplasty was estimated at $7000.2 The variations in costs of care among insured and uninsured populations not only create gaps in care for transgender patients, but also form a barrier between the transgender community and access to such services.

Controversy exists on whether gender-affirming treatments should be federally funded through insurance programs such as Medicaid or Medicare. For instance, gender-affirming treatments can be viewed as a cosmetic rather than a medical procedure.15 In a study by Solotke et al,6 high variability was found in Medicare prescription drug plan coverage of hormonal therapies for transgender individuals. Although the Affordable Care Act prohibits discriminatory policies based on gender identity, health insurers can deny coverage for gender-affirming treatments due to variations in legal interpretation.16 For example, insurers can refuse to cover preventive sexual and reproductive health care or pregnancy care if the patient is registered as a male on their insurance.17 The study by Padula et al13 showed that insurance coverage for transgender treatments is affordable and cost-effective. In line with this, gender-affirming treatments should be covered through federally funded insurance plans to reduce existing health care disparities among transgender patients. As evidenced by research, the high costs of treatment increase the risk of depression, unemployment, HIV infection, suicidality, and substance abuse among this group. Further policies should be implemented barring insurance companies from denying insurance coverage for transgender patients who will benefit from hormone replacement therapy and gender-affirming surgery, thereby reducing negative consequences.

National and State Policies

Transgender adults, compared with cisgender adults, have higher rates of mental health issues including depression and anxiety.18 The 2015 US Transgender Survey (n = 27715) performed by the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) demonstrated this disparity in mental health, with 39% of respondents experiencing serious psychological distress (identified by participants reporting how often they experienced feelings such as hopelessness or worthlessness) compared with 5% of the general US population. The gravity of the situation was highlighted by the fact that 40% of the respondents attempted suicide in their lifetime, which is 12 times the rate of the general US population of 0.6%.8

To improve these statistics, transgender patients’ access to quality health and mental health care must be prioritized. The list of current barriers limiting access to quality health care are ten-fold when considering financial and socioeconomic barriers but can also be attributed to structural discriminatory treatment toward this marginalized population. One example of this treatment includes denial of insurance coverage in relation to gender-transition care or even routine care due to identifying as transgender: 55% of NCTE respondents were denied coverage for transition-related surgery and 25% were denied coverage for hormonal therapies. Another example pertains to negative experiences due to physicians refusing treatment or lacking expertise in transgender medicine, with 33% of NCTE respondents reporting at least 1 negative experience with a health care provider related to being transgender.8 These acts of discrimination toward transgender patients should make apparent to the US government the need for prioritizing legislation that promotes their access to care.

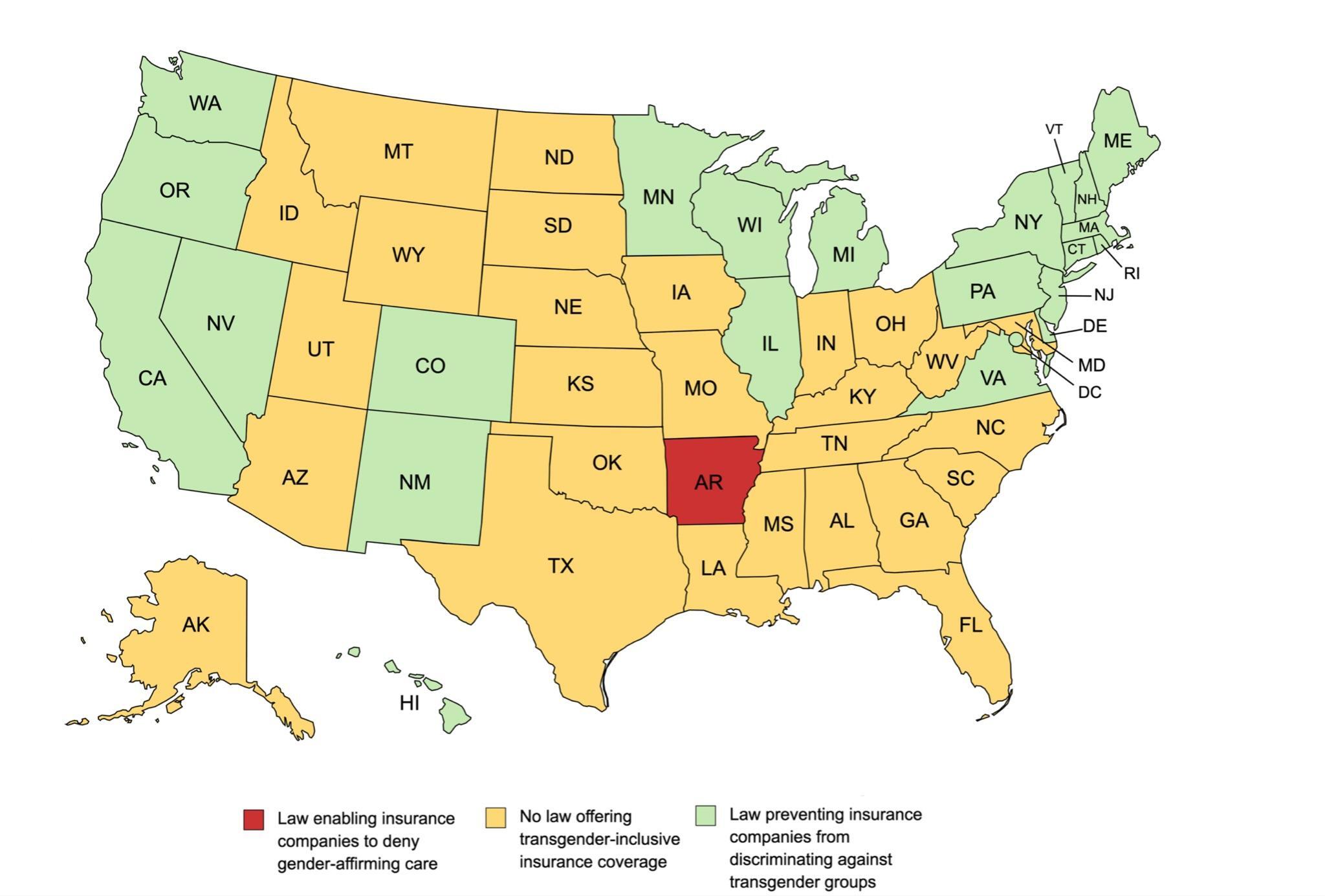

In May 2016, under the Obama administration, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Civil Rights (OCR) implemented Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, a nondiscrimination provision preventing discrimination in health care on the basis of race and ethnicity, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability in federally funded facilities or programs, including hospitals receiving Medicaid or Medicare funding. The passage of this provision addressed the discriminatory health care treatment toward transgender patients and made previous practices illegal, such as denial of health care or coverage to individuals on the basis of gender identity or denial of treatment related to gender transition.19 This prevents the exclusion of health care services to transgender individuals, but does not require health plans to provide specific services. This also only applies to federally funded health care coverages; many private US health insurers continue to deny transgender coverage for services citing financial concerns (Figure 1).7

Since its implementation, Section 1557 has been met with opposition from state legislatures and was affected by the transition from the Obama administration to the subsequent Trump administration. For example, in December 2016, a Texas judge issued a national injunction prohibiting OCR from enforcing Section 1557 on the basis of gender identity. In April 2018, the Trump-appointed director of OCR coincided with the decision by drafting a proposal eliminating the nondiscrimination protections based on gender identity and removing insurance companies from having to comply with Section 1557.18 The Trump administration continued to roll back legislation and eliminated protections for the transgender population in health care, while also adopting a stance to defer to states on transgender legislation.20

While 18 states and the District of Columbia have passed transgender protections in health care, these policies are absent throughout many states, with some states passing additional legislation preventing the enforcement of Section 1557’s nondiscrimination laws (as highlighted by the previous Texas injunction).20 A study by White Hughto et al4 on state-level transgender care refusal found that 33% of Southern states were in the top 10 highest transgender care refusal states. This study also found voting behaviors to be an indicator of transgender care refusal; states holding high percentages of conservative voters correlated with high refusal rates.4 Most recently, in April 2021, Arkansas became the first state to ban gender-affirming care for transgender minors, which included noninvasive hormonal therapy; this was done despite the bill being vetoed by its governor. Identifying factors that contribute to transgender health care discrimination, such as geographic area and political ideology, provides areas of focus when determining where educational efforts and resources should be allocated to mitigate these disparities.

Despite the fact that US health associations, such as the American Medical Association and American Psychiatric Association, have defined gender-affirmative care as medically necessary, efforts on the national and state levels to improve transgender health care coverage are variable and will require continued advocacy on behalf of pro-LGBTQ organizations and the private sector.7 A win for the transgender community came in June 2020 when the US Supreme Court ruled in Bostock v Clayton County that employment discrimination based on sex, including gender identity and sexual orientation, violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.21 Because Title VII applies to employer health plans, an employer’s refusal to cover gender-affirmative care could be considered illegal under Bostock v Clayton County. This will force private-sector employers to expand their health insurance plans to include transgender-inclusive coverage for the 53% of transgender adults with employer-based insurance. However, this does not take into consideration the transgender adults who are unemployed at a rate 3 times higher than cisgender adults.22

With the Biden administration holding the US Senate and House of Representatives majority, it will be important to pass antidiscrimination legislation protecting the transgender community and improving its accessibility to health care on a national level. Continuing research into transgender health care disparities at state and local levels will identify geographic regions where mistreatment is likely to occur. Resources including mental health counseling and social workers should be more prevalent in these areas. As health insurance coverage is only one of the structural barriers affecting this population, the medical community should lead the way in addressing the public health crisis against transgender patients.

Interventions Against the Status Quo

Though transgender patients in the United States face cost and legal barriers to health care, they also face additional obstacles at the social level. Transgender patients have avoided seeking medical attention for acute care due to a negative experience in the past or for fear of being discriminated against because of their gender identity.23 A survey of 4049 trans-identifying patients revealed that more than 50% (n = 2042) of the respondents had delayed seeking medical treatment.24 This is a striking difference in comparison with the 20% cisgender majority in the United States.25 Half of the trans-identifying patients who had postponed seeking care attributed their delay to affordability (n = 1013), while the other half (n = 1029) attributed their delay to fear of discrimination from doctors or other health care providers.24 A survey from the American College of Emergency Physicians including 399 respondents found that even though the majority (n = 343; 86%) of the physicians felt comfortable using the correct pronouns when speaking to transgender patients, only 3% were aware that emergency medicine physicians routinely performed inappropriate examinations that led to discomfort among transgender individuals.26 An inappropriate examination was defined by patients to include provider gawking, persistent staff focus on genital examinations, unnecessary history taking about gender-related surgeries, sexual history, assumption of sexually transmitted infections, drug use, psychological disorders, and the use of the patient for “teaching” that was interpreted as being put on display.26 Additional questions within the survey discovered that only 26.1% of physician respondents were familiar with the most common gender-affirming surgery for female-to-male patients; only 9.8% of the respondents could identify the most common gender-affirming medication that male-to-female patients use.26 These data showed the striking disconnect between physicians and gender-nonconforming patients and drew attention to possible areas of intervention to improve this matter.

Inclusivity in the Clinical Environment

Gender-exclusive language and representation in clinical care settings, such as family planning centers or sexual and reproductive health clinics, can isolate and stigmatize transgender patients. Moseson et al17 provided the example of a transgender female patient walking into a “women’s health” center advertising language and imaging only relevant for cisgender women. The exclusivity of this environment is further pronounced during instances of improper pronoun usage by clinic staff when addressing a transgender patient. Though the exclusivity of the clinic may be unintentional, only catering to the identity of cisgender women could dissuade a transgender woman from seeking further medical care at the clinic and contribute to hesitancy about seeking help in any health care setting.17

To create more inclusive environments for transgender patients, clinics and hospitals can make a conscious effort to include representation and literature pertaining to transgender care; steps can also be taken to create gender-neutral restrooms. In patients’ initial intake forms, questionnaires should include questions pertaining to gender identity and sexual orientation. Faculty and staff should be instructed through required trans-conscious educational training modules to raise awareness of the transgender community, including the importance of addressing patients by their preferred pronouns. Additionally, greater outreach should be extended into increasing LGTBQ representation in the health care profession.

Medical School Education

It has been suggested that to improve the outcomes of transgender patients, medical students should be given a standardized curriculum pertaining to transgender care throughout their normal medical training.9 A multi-institutional study involving 170 allopathic and osteopathic medical schools in the United States included 4262 second-year and above medical students who were given a questionnaire to assess their preparedness and comfort in transgender-related topics. Of the 4262 participants, a majority (n = 2866; 67.2%) rated their school’s LGBTQ curriculum as “fair,” “poor,” or “very poor” (Figure 2).27 Despite these responses, students reported feeling “more prepared” (n = 2662; 62.6%) after their second year of medical school, and even more so after their third year in training.27 Though their degree of preparedness after their second and third years of school was not outlined, it could be partly due to the clinical exposure to patients and the knowledge gained from other health care providers during clinical rotations.

Research has shown efforts to incorporate transgender curriculum into both undergraduate and graduate medical education, though it is still in its early stages. Only 16% of Liaison Committee on Medical Education–accredited academic practices reported a comprehensive LGBTQ-competency training program, whereas 52% reported no LGBTQ training at all.10 It is unclear how much LGBTQ-related curriculum is taught at each individual medical institution or to what extent the depth of topics is covered, but there needs to be an increase in awareness and standardized instruction. Future physicians should be well-equipped to treat the specific needs of transgender patients in the community and fully address the psychological and endocrine-related aspects of their care. There are limited amounts of studies outlining the LGBTQ or transgender-related content that is taught to medical students in their preclinical years or how doing so would translate into their practice as physicians. More research is required to further assess the relationship between these 2 variables.

Continuing Medical Education

Continuing medical education (CME) allows practicing physicians to stay current with medical interventions, techniques, and research. It has implications to improve and maintain the competency of physicians who encounter transgender and gender-nonconforming patients just as it would any other medically related topic covered by CME. CME has been shown to provide some degree of both short- and long-term advantages in retaining and acquiring clinical knowledge, whether that be in surgical techniques or within the practice of medicine.28 This idea should translate to acquiring new clinical knowledge pertaining to proper transgender health care as well. When correctly implemented, CME provides a resource for senior physicians to engage in valuable learning opportunities in the hopes of improving transgender health inequities.3 Additionally, CME has the potential to start a “trickle down” effect wherein medical students and other health care providers could benefit from the knowledge that physicians gained from participating in CME.3

The only issue that CME presents is that more often than not, physicians take a self-directed approach when choosing which CME courses to partake in, choosing topics that are familiar to them and that reinforce old practices. To increase competency in novel topics, such as LGBTQ patient care, a topic-targeted CME structure has been implemented in some areas and was seen as more effective in improving physician competency in new, unfamiliar topics.29 There is a basic lack of clinical knowledge amongst physicians when it comes to treating transgender patients.26 A more organized approach toward CME, specifically in LGBTQ-related areas, should be taken into account to support the growing population of individuals identifying as LGBTQ or gender nonconforming.

CONCLUSIONS

Among transgender patients, disparities with respect to treatment costs, health care policy, clinical inclusivity, and medical education remain. Transgender individuals face greater risks of psychological distress and suicide resulting from gender misalignment and gender dysphoria, highlighting the urgent need for access to quality health care.8,12 Treatments proven to alleviate these mental health disparities include hormonal therapies and gender-affirmative surgeries, but the current costs make it difficult to access this care without health insurance coverage. For example, the cost of surgical procedures for transgender females without insurance can range up to $23 000, while costing $7000 with insurance coverage.2 However, instances of insurers lacking or outright refusing coverage for gender-affirming treatments poses an additional barrier for transgender patients seeking access to medically necessary care. Coverage for transgender procedures remains variable and highlights the need for national and state legislation enforcing health insurance policy compliance.

While Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act attempted to provide federal guidance preventing discriminatory practices on the basis of gender identity, state-issued policies counter its implementation and limit transgender patients’ access to care. Specifically, states like Arkansas and Texas attempted to eliminate protections outlined in the Affordable Care Act.20 Future legislation should close statewide loopholes that disallow transgender patients from receiving insurance coverage and expand procedure options under federal assistance. Future protections for both trans-males and trans-females should consider specific nondiscriminatory policies. Additionally, enforcement of Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act in the private sector remains challenging, because the provision only covers federal insurance policies.20 Current legislative focus should attend to the needs of transgender individuals by outlining guaranteed coverage and treatment plans. The current gap exposes the need for continued advocacy on transgender rights, preventing the exclusion of transgender patients from accessible and affordable health care.

Because health care policies can contribute to social stigma and misunderstanding of the transgender community, medical institutions should embrace the transgender public health issue and increase the likelihood of physician interactions. Physicians educated with LGBTQ-focused medical curricula lessens the biases that may result in transgender avoidance of care. By including LGBTQ curricula in CME courses, physicians are incentivized to learn and understand the transgender patient perspective, diminishing the rate of missed appointments, poor patient interactions, and mental health–related issues.29 Although data revealed that preclinical medical students did not receive satisfactory education on LGBTQ health care, they highlighted an opportunity to review medical school curricula and expose students earlier in their education.27 Patients are more willing to engage with a physician of similar identities, underscoring the need for LGBTQ physicians and representation in clinical environments.17 In brief, improving medical school education and adapting ongoing CME training gives an opportunity to make physicians more knowledgeable and aware of transgender health care issues.

Overall, transgender patients remain excluded from many of the opportunities that cisgender patients are afforded. Bolstered medical education for both students and current physicians provides an opportunity for increased awareness of LBGTQ disparities. By extending representation of LGBTQ physicians, improved quality of care can be achieved. Additionally, legislative review against nonadherence to the Affordable Care Act could alleviate the financial burden of care against those in the transgender community. The mental health burden on transgender individuals remains high. With new federal administrative policies, adequate funding and resources can address patients with gender dysphoria. The current disparities faced by the transgender population pose a necessary and urgent need for legislative and academic attention. Perpetuating these inconsistencies in care would further the harm outlined earlier in this analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.