Introduction

As the United States continues to grapple with the rising health burden and death toll of COVID-19, another epidemic has been systemically harming the public health and safety Df US-based people for decades: structural racism. In a public health context, structural racism is embedded in US systems and institutions as a conventional practice that is designed to provide privileged groups with better access to the resources needed to be healthy while differentially disadvantaging or otherwise neglecting racial and ethnic minority groups.1 These resources may include, but are not limited to, quality housing, higher educational attainment, economic stability, job opportunities, affordable health care, and healthy food options. In turn, this inequitable access to resources results in a disproportionately high incidence of adverse health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States.

The evidence to demonstrate the association between structural racism and negative health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority groups has been identified and quantified by researchers in abundance.2–8 Racial residential segregation, one of the few comprehensively studied facets of structural racism, has been associated with reduced access to quality education, fewer employment opportunities, and lower socioeconomic status in segregated neighborhoods.2 Furthermore, the consequences of racial residential segregation have been empirically linked to specific poor health outcomes, such as low birth weight, elevated breast and lung cancer mortality rates, obesity, and overall poorer health.3–6 Population health data across US cities continue to substantiate these findings and make visible the persistent and disproportionate burden of negative health outcomes on racial and ethnic minority communities. For example, Washington, DC, boasts one of the country’s highest percentages of gentrified neighborhoods of any city in the United States in concurrence with extensive health disparities between Black residents and White residents.7,8

While these disparities have largely persisted in silence for decades, the plague of systemic racism on health has become increasingly apparent in the wake of record protests demanding justice for the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others. Moreover, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on African American people has further elucidated the devastating consequences of racism on health. These circumstances have brought racism into the spotlight of national attention and created a sense of urgency to address racism as a public health issue.

In response to this sentiment and the recent momentum gained by racial equity movements, such as Black Lives Matter, various local health agencies (LHAs) and governing bodies throughout the United States have openly declared racism a “public health crisis” or “public health issue.” Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was one of the first US counties to make such a declaration in May 2019, but the widespread adoption of this declaration is unprecedented in its current scale.9 The American Public Health Association (APHA), which tracks declarations of racism as a public health issue, now lists more than 200 public health agencies, city councils, and state legislatures across more than 30 states—up from only 7 at the end of 2019.10,11 For many, these widespread declarations of racism as a public health crisis are a step in the right direction to addressing structural racism and the chronic upstream problems contributing to racial health disparities. However, these declarations do not equate to any specific changes in public health policy, funding, or authority for many jurisdictions. While governing bodies have introduced various strategies in response to these declarations, such as organizational policy changes, diversion of funding to public health, and accountability measures, there is little consistency between responses across jurisdictions.12 Therefore, the contemporary nature of this declaration and the diversity of responses pose an important question: Is declaring racism a public health crisis mere rhetoric or a true catalyst for change?

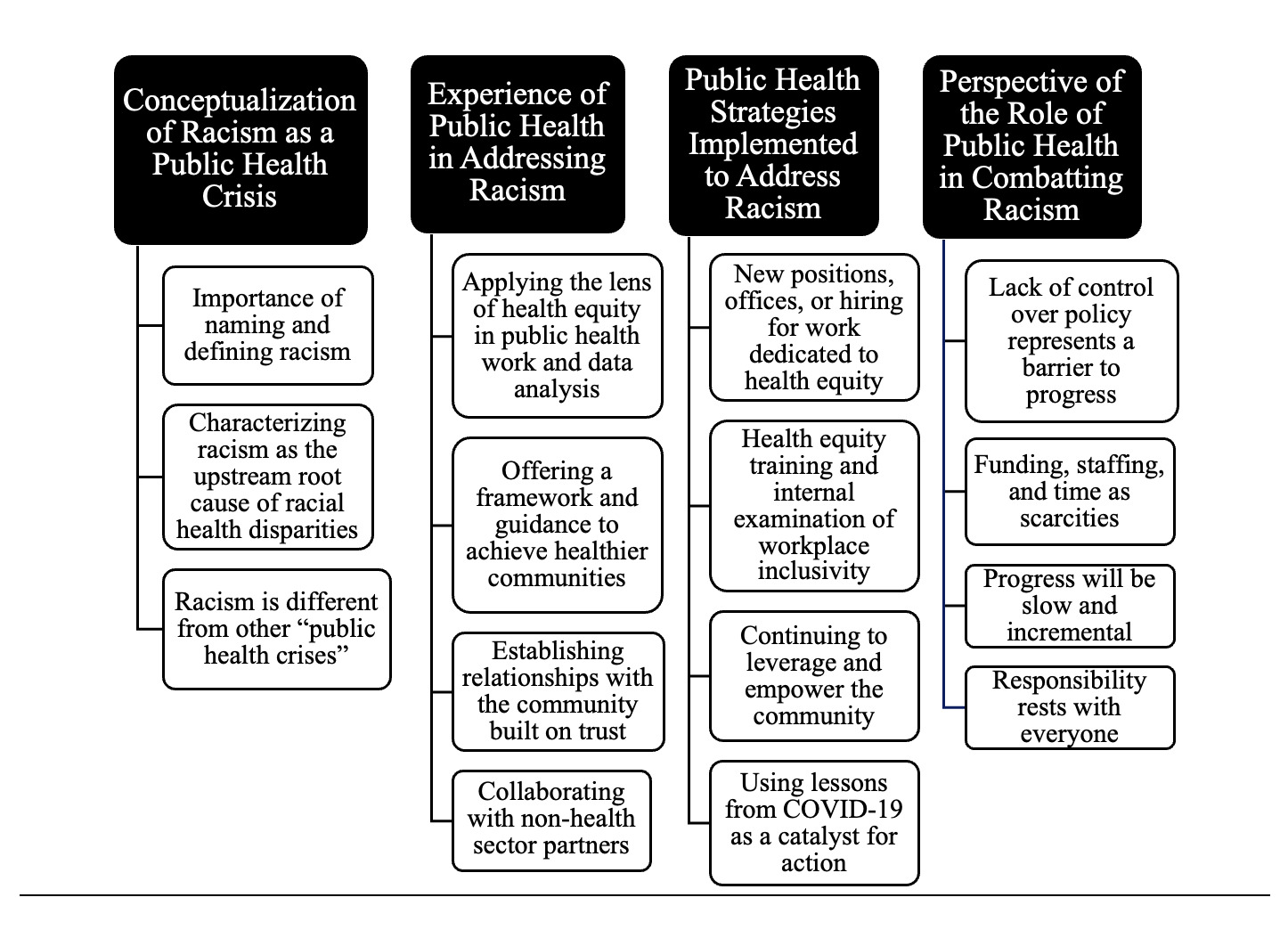

This article attempts to explore this question based on findings from key informant interviews conducted with public health officials working for LHAs in the Washington, DC/Maryland/Virginia (DMV) area. The objectives of these interviews were to elucidate (1) the perspective of DMV LHAs regarding the concept of racism as a public health crisis, (2) the experience of DMV LHAs in addressing racism, (3) the novel strategies or changes that DMV LHAs are implementing to address racism and their perceived capacity to do so, and (4) the overall perspective of DMV public health officials as to their role in combating racism. By providing this information, this study aims to improve awareness of how US public institutions are responding to the current public sentiment and implementing actionable changes to address structural racism with the urgency that it deserves.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This study was reviewed by the Georgetown University institutional review board (IRB ID: STUDY00002685) and received an exemption on July 21, 2020. Interviews were conducted from July 2020 to September 2020. The scope of the interview setting was limited to the DMV area.

Participants

Public health officials were identified via government-sponsored public health websites (eg, dchealth.dc.gov) and their associated directories or through personal connections mediated by the principal investigator. Individuals who (1) held credentials that attested to significant knowledge of public health and experience in the field and (2) were English-speaking were targeted for recruitment. Eleven high-ranking public health officials serving the DMV area, such as county health officers and district directors, were selected and compiled into a key informant master list. Subsequently, these individuals were all recruited via email correspondence. Snowball sampling was used in some instances in which key informants forwarded the recruitment materials to colleagues or other individuals working in their respective public health organizations. Following the recruitment of key informants and ensuing snowball sampling, 15 individuals had been contacted, 9 did not respond to email correspondence, 2 declined the interview invitation, and 4 accepted, underwent the consent process, and were subsequently interviewed. The initial target analysis sample was 5 participants. The stopping criteria included 3 consecutive interviews with no new themes emerging, which would reflect data saturation.

Interviews and Data Analysis

The principal investigator conducted semistructured key-informant interviews with participants via the remote video conferencing interface Zoom (Zoom Video Communications). No relationship with participants was established before the interview; however, participants were aware of the purpose of the research. Interviews were conducted alone with the participants in their office or home setting. Interviews were video- and audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Background information (eg, position title, number of years in position, work experience) was obtained verbally from the participant. The interview script was composed of open-ended questions designed to elicit dialogue to achieve the 4 objectives previously outlined. Written consent was obtained from all participants to publish background information and interview responses. In the interest of full disclosure and clear communication, verbal consent regarding the potential publication of interview data was also obtained before initiating the recorded interviews. Interview length averaged 33 minutes, ranging from 28 to 44 minutes.

Data analysis of interview transcripts was conducted using qualitative thematic analysis, following steps outlined by Nowell et al.13 Each interview was independently examined by the principal investigator. No specific software was used for data analysis. First, the principal investigator was familiarized with the transcribed data, derived initial codes from the data, and manually recorded these codes. These preliminary codes were then analyzed using an inductive approach, in which the identification of themes was strongly linked with the interview data with little relation to the specific questions asked of the participants. Subsequently, all themes were reviewed by the principal investigator for consistency, validity, and coherency of patterns. The principal investigator alone conducted all elements of data analysis, including coding, analysis, theme identification, and review.

Results

Description of Participants

Participants in this study had a wide array of work backgrounds, with job titles ranging from population health managers to county health officers. The final pool of participants represented 4 county and/or state health departments distributed across Maryland and Virginia. Participants held mixed education credentials consisting of 2 participants with medical degrees and 2 masters of public health (MPH). Previous work experience varied greatly between individuals with medical degrees. One participant with a medical degree described over a decade of patient care at community organizations, such as federally qualified health centers, prior to becoming involved in public health in recent years. In contrast, the other participant with a medical degree has been working in public health for more than 20 years. Previous work experience was similar between individuals with MPH degrees. Both MPH participants held backgrounds in epidemiology with involvement in an assortment of public health realms such as infectious disease surveillance, community health assessments and improvement plans, communications strategy, and community outreach. Given the relatively small sample size of this study and the sensitivity of topics explored in these interviews, other demographics of participants (eg, race, ethnicity, age, gender) are not reported to preserve the anonymity of interviewees.

Conceptualization of Racism as a Public Health Crisis

Three key themes were identified in the data collected from the DMV public health officials regarding the concept of racism as a public health crisis:

Importance of Naming and Defining Racism. When asked to describe the meaning and significance of the declaration of racism as a public health crisis for their respective organizations, participants cited the importance of “naming” or “defining” racism as a key step in progress towards racial health equity. This perception is highlighted across multiple interviews, such as in the following example:

I think, at the local level, for a long time, we have tried to examine racial equity and social justice. As a whole, that is really what public health is all about. But I think that there has been a lot of reluctance to call it ‘racism.’ I think, for us, that having a formal declaration or even just bringing this more to the forefront will enable us to take more action and to be more accountable.

- Public health official 1

Characterizing Racism as the Upstream Root Cause of Racial Health Disparities. All interviewed public health officials independently endorsed the characterization of racism as a “root cause” of racial health disparities. Importantly, however, participants also emphasized the need for a further shift to this common perspective:

…to take an analogy from medicine, if you treat the symptoms and not the cause, you’re not going to get [to health equity]. And this is the same idea, if we really want to get at the root cause [of racial health disparities], racism is one of them and it is a big one. It’s not the only one, there are other issues, but if we can’t even name it, we will never get there.

- Public health official 2

In various forms, participants also stressed an understanding that achieving health equity for their respective communities requires a focus of attention on the upstream factors that contribute to poor health outcomes, particularly in racial and ethnic minority communities. Participants noted that the role of racism in this equation is often complex and interwoven:

There is an understanding [in our health district] of the disproportionate impact that racism has on people of color in economics, education, [etc]. They are all interrelated in which low education [begets] poor job quality which [begets] low income, substandard housing, and [ultimately] health issues…if our solutions are [simply] more access to health care, it just builds a pipeline for more people to get into health care … It’s not the right place to be if we can prevent it.

- Public health official 3

Racism is Different From Other “Public Health Crises.” Participants described racism as a unique challenge for public health efforts that differs from public health crises in the typical sense. Compared with other public health issues, such as the opioid crisis, racism was described as a more systemic problem requiring change in larger societal structures. Concisely put, one participant says:

It is tough to compare because it seems the opioid epidemic has only been deemed a ‘crisis’ because the public face has affected many White Americans, and that is why it has received the attention that it has—as opposed to other drug issues, even within our own community, that are more prevalent than opioids but are receiving less attention by local, state, or the federal level because it is experienced more by Black Americans or people from other ethnic origins. The comparison to other crises is that racism is really at the heart of why we see these exacerbations [among racial and ethnic minority communities], therefore, it is difficult to extricate them.

- Public health official 1

Additional examples of the conceptualization of racism as a public health crisis can be found in Table 1.

Experience of Public Health in Addressing Racism

Four key themes were identified from participants regarding their LHA’s experience in addressing racism:

Applying the Lens of Health Equity to Public Health Work and Data Analysis. Participants across all interviews described efforts by their respective LHAs to infuse a health equity perspective into decision-making processes, data analysis, and the development of strategies such as community health improvement plans (CHIPs). Because of the particular relevance of COVID-19 during the time of these interviews, participants often provided examples of this in relation to the pandemic:

If we think about [our] health equity working group, people have [been making an effort] to apply more of a racial equity lens to the data that we capture and how we, [for example], determine where we need to set up [COVID] testing events and what populations we need to target.

- Public health official 4

Moreover, participants described health equity as an all-encompassing process that can be applied to the entirety of public health work:

Health equity is the process through which we make [public health] decisions. It is not one of the things we are doing, it is how we are doing the work.

- Public health official 2

Offering a Framework and Guidance to Achieve Healthier Communities. When participants were asked to identify how their respective LHAs were well-suited to address racism, responses were mixed, but mainly emphasized the ability of public health to provide a structured approach to addressing health problems (ie, creating solutions) and to offer guidance through their areas of expertise (eg, data analysis):

There’s a paradigm to address any public health problem: (1) you want to collect data to examine the problem, (2) you want to assess risk and protective factors, use evidence-based solutions, integrate, and scale-up. Public health offers a framework to address a problem (such as racism) from a more structured perspective. It is part of why we saw responses to the opioid crisis work.

- Public health official 2

Establishing Relationships With the Community Built on Trust. Participants identified building relationships and establishing trust with the community as crucial components of public health efforts in multiple respects. In particular, participants described the declaration of racism as a public health crisis as an opportunity to (1) further break down the barriers of historical distrust between the health sector and racial and ethnic minority communities and (2) continue to earn the trust of constituents and work towards mutual interests.

One of our key missions is to not do things without community input and feedback…joint decision-making is our best way of being able to share our power with community members so they are also decision-makers… We could do things a little simpler and work without that community engagement piece but we don’t see that as an effective strategy. Especially with the history that public health and medical institutions [have] of mistreating communities of color and lack of respect—we are really trying to break through that.

- Public health official 1

Participants also noted the importance of community input in the development of public health policies, programs, and initiatives, particularly in regard to the development of community health assessments (CHAs) and CHIPs:

When we conduct our community health assessments, we send a survey to our residents to ask them, ‘What are the greatest strengths of the community?,’ ‘What are the biggest health challenges?,’ ‘What would most improve the quality of life in the community?’ We also do ‘community conversations,’ which entails a type of town hall where we communicate our work to the residents and ask for their feedback. It is a very interactive process to conduct our community health assessment and constructing an improvement plan… We always try to engage residents of [our health district] because we never want to start an initiative without buy-in from the community… They are not successful if we do not.

- Public health official 4

Collaborating with Non–Health Sector Partners. Participants frequently cited their measures to engage with non–health sector partners by building multisector advisory coalitions and leadership teams. These efforts were implemented to promote cross-sector understanding of public health issues and to work mutually towards health improvement. Participants often described these collaborations with non–health sector organizations as the norm, rather than the exception:

In 2009, recognizing and better understanding the role of social determinants, we thought it was important [to create] a Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) coalition. We brought over 130 organizations and partners to the table to educate, expose, and have conversations around social determinants of health and how it impacts [public] health. Why did we do that? So that we could all be on the same level playing field as we looked for solutions.

- Public health official 3

Additional examples of experiences of public health in addressing racism can be found in Table 2.

Public Health Strategies Implemented to Address Racism

Four key themes were identified from participants regarding new strategies or policies being implemented to address racism in the public health sphere:

New Positions, Offices, or Hiring for Work Dedicated to Health Equity. When participants were asked to identify novel strategies being operationalized to address racism as a public health crisis, they frequently drew attention to recent hiring or the creation of new positions and offices dedicated to health equity work. Importantly, all participants independently identified various manifestations of this theme:

The city recently hired its first racial and social equity officer, which is a high-level leadership position in the city manager’s office, and her role is to really focus on those policy and systemic issues.

- Public health official 1

Health Equity Training and Internal Examination of Workplace Inclusivity. An additional strategy identified by participants working in the health districts of the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) included racial equity and workplace inclusivity training:

…[W]e have partnered with the Institute for Public Health Innovations, which will provide our coalition with equity training around the history of racism, including systemic racism and anti-Black racism, along with ways that we can do better in applying a racial equity lens to our initiatives moving forward.

- Public health official 4

Furthermore, the same participant also mentioned an internal survey of all VDH health districts aimed at assessing employee perceptions regarding the organization’s diversity, inclusion, and equity:

At the state level, VDH has just sent a survey to all the health districts regarding diversity, inclusion, and equity. I think the point of it is to take an inventory of all the staff and how they feel working [in VDH]. Some of the questions asked were ‘Have you experienced discrimination at work?’ or ‘Have you felt uncomfortable or have you wanted to leave work?’ or ‘What efforts can be made to have a more inclusive workforce?’ If we are going to be the face of racism as a ‘public health issue,’ then I think this is a way to look internally to make sure we are walking the walk ourselves.

- Public health official 4

Continuing to Leverage and Empower the Community. When questioned regarding the sustainability of any future strategies being implemented, responses were mixed. However, consistent with the theme of collaborations between public health, non–health sector partners, and community members, participants alluded to the importance of leveraging what is already in place:

We have to respect and start with the community as opposed to ‘do for’ community. When you ‘do for’ the funding has to come from here [the health department]. But when you ‘do with’ then you are able to leverage what exists! A lot of times, things [eg, programs] fall apart because they are not sustainable and sustainability is a big thing… The goal is to work with the community in a way that you empower them and work towards a common goal—that is the hardest frontline work. But when you are successful with that, it becomes a domino effect where [the results] keep going and going. As an agency, we are doing many-fold more with less because of community engagement.

- Public health official 3

Using Lessons From COVID-19 as a Catalyst for Action. Due to its particular relevance to the operations and strategic planning of public health agencies at the time of these interviews, COVID-19 was frequently noted as a catalyst that sparked new efforts to address racial health inequity. In particular, participants endorsed an understanding among their respective organizations that the racial health disparities seen in the COVID-19 outcomes data can be applied to many other health conditions as well:

I think, for public health and for everyone, we can take a lot of these lessons learned from the current pandemic as it has laid bare these long-standing issues. I think that the work that is being done around [COVID] can be applied to other health conditions or long-standing health problems… These lessons are very important and we need to make sure we carry them forward.

- Public health official 4

Additional examples of the public health strategies implemented to address racism can be found in Table 3.

Perspective on the Role of Public Health in Combating Racism

Four key themes were identified from participants regarding their perspective on the role of public health in dismantling structural racism:

Lack of Control Over Policy Represents a Barrier to Progress. From a public health perspective, policy was identified by most participants as one of the key barriers to their progress to address racism. Participants identified the problem of policy in a variety of contexts, but mainly emphasized that (1) LHAs often lack control over key policy measures (eg, housing, education) that affect the health of their constituents and (2) bureaucracy often limits the ability of public health officials to make substantive changes to policy at the local level:

Where I don’t think we are well-suited is that we do not control the levers that are going to get at a lot of these issues in racism—housing policy, economic policy, how social services are constructed, job protections—these are all expansive issues. The criminal justice system is another factor outside of our control. So, what we can do is highlight and push at it, we can help organize it, but at the end of the day, it requires pretty much everybody to want to be a part of that and to find a solution. So, there is a limitation: when we declared racism as a public health issue it was done in concert with the county executive and is not something we do on our own. In fact, it wouldn’t go anywhere if we do it on our own. If we have the county executive to believe that [racism is a public health issue] and back it, it gives us the opportunity to put some muscle into it.

- Public health official 2

Funding, Staffing, and Time as Scarcities. Most participants noted that public health work in their respective organizations is often strained by the limitations of money, personnel, and time. Furthermore, participants often spoke passionately about their desires to expand their team staffing or to increase the funding for community outreach initiatives:

In terms of where we are lacking in our capacity, which I believe is typically true for all public health initiatives, staffing, funding, and sometimes leadership can often be barriers. [Our] health district is already pretty low in our staff capacity, which tends to be the nature of public health being a transient community with a lot of turnover. For me, I try to do these population health initiatives and efforts but I am working as a team of one person. I would love to potentially have more people on my team or someone who is more dedicated as an equity or diversity officer—that expertise [would be helpful] for my team. As far as funding, it is a little bit out of my hands.

- Public health official 4

Progress Will Be Slow and Incremental. Seemingly speaking from experience, public health officials described the future challenge of addressing racism as a public health crisis as a long and “painstaking” process. More specifically, participants characterized racism as a unique type of public health issue that requires perseverance and commitment to maintaining momentum:

Generally, ‘crises’ [in public health] tend to end quickly, but [with racism] we are not going to be done in a couple of years. It’s going to take decades, to be honest about it… The nature of change like this is that you keep putting out what you need to put out until someone is ready to take it up—this is a long campaign. Having that rigor and dedication to keep pushing [is key].

- Public health official 2

Responsibility Rests With Everyone. When clarifying the role of non—health sector participants in these initiatives moving forward, participants stressed that the responsibility cannot rest on public health alone. Rather, participants believed that it is the duty of individuals in all domains to take part in this mission for progress and change:

One of the things that many public health officials will tell you: public health is not just the health department. Public health is what we do together as a society to create the conditions in which people can be healthy. It is multifaceted and you need all those actors I talked about (education, housing, transportation, elected officials, public safety organizations, community-based organizations). The African proverb ‘It takes a village’ signifies what public health is—it is a village.

- Public health official 3

Additional examples of the perspective on the role of public health in combating racism can be found in Table 4.

Additional Themes Identified

Disagreement Regarding the Importance of Semantics. During the interviews, there were discrepant responses among participants when asked whether the declaration of racism as a public health emergency rather than a crisis is a significant distinction from the perspective of their LHAs. Some participants demonstrated hesitancy to the term emergency due to the meaning that it invokes in public health:

We used the term issue; some use crisis and some use emergency. I don’t like the term emergency because I work in public health where it is a statute and invokes particular powers of the state. At the end of the day, when you say racism is a public health ‘x,’ ‘What are you going to do about it?’ is what I am far more concerned about… The money and commitment are much more important than linguistics for a crisis that goes on for decades.

- Public health official 2

Others, however, believed that the distinction is significant and useful to future efforts:

I think that it is. The only thing is that when we typically call something a public health emergency, it is more short-term, while this is a more sustained effort. But I think it communicates the importance of it and could help to shift around resources, whether it be money or personnel to be more explicit with our efforts and to have more of a driving force behind it.

- Public health official 4

Additional examples of the these additional themes can be found in Table 5.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate a shared understanding among public health officials in the DMV area regarding the influence of racism on disparate health outcomes, which has broadly manifested in declarations of racism as a “public health crisis” or “public health issue.” In particular, participants expressed that their organizations understand the implications of upstream social determinants of health (eg, education, housing) for their racial and ethnic minority communities and are aware of the racial health disparities that have been highlighted in public health literature for decades.14 Despite this, participants in this study acknowledge a hesitancy in public health to label these disparities, until recently, as “racism.” Consistent with this sentiment, Hardeman et al15 pointed out a peculiar absence of the term institutionalized racism from public health abstracts and publications and called on researchers to be more explicit about the impact of racism on health.

These new initiatives to name, define, and characterize racism as a root cause of racial health disparities indicate a fundamentally important step for racial equity initiatives and health disparities research. The APHA endorses the importance of this step under its key principles for advancing health equity, stating, “Being explicit is key to ensuring vulnerable populations receive the social and economic resources needed to be as healthy as possible. It is also crucial to be explicit in order to ensure that disparities in health are not worsened as a result of ambiguity.”16 Declaring racism as a public health crisis does not eliminate the climate of controversy surrounding racism that has prevented this explicitness for decades. There is considerable work to be done in the United States to educate the public and to motivate all organizational sectors to examine prejudiced policies and societal structures that disadvantage racial and ethnic minority communities.17 However, it is apparent from the data in this study that the current momentum gained by racial equity movements across the United States has motivated the efforts of DMV LHAs to work towards structural change.

According to study participants, LHAs offer the framework to address racism by collecting and analyzing health disparities data, building large-scale health equity initiatives, and establishing partnerships with the community and non–health sector organizations. Participants emphasized the application of a health equity lens to public health work and data analysis with a particular focus on the development of CHAs and CHIPs. Indeed, the utility of CHAs and CHIPs in improving health outcomes is endorsed by both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and APHA and has been required of public health organizations by the Public Health Accreditation Board since 2013.18–20 While studies establishing causation between the use of CHAs and CHIPs and improved health outcomes are limited, evidence supports the role of these accreditation requirements in generating significant increases in community engagement and collaboration with non–health sector partners.21

Consistent with these findings from previous studies, the data demonstrate a strong conviction from participants regarding the importance of community engagement when addressing public health issues such as racism. In fact, the data suggest that collaborations with the community and non–health sector partners are one of the most important aspects of public health work that LHAs in the DMV area strive to achieve. One unique example cited by a participant in this study is the One Fairfax resolution, a social and racial equity policy of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors and School Board that was passed by Fairfax County, Virginia, in 2017. The policy explicitly outlines the crucial nature of community engagement in the development, implementation, and evaluation of public policy, with the ultimate goal of advancing racial equity, stating, “To foster civil discourse and dialogue, community engagement shall ensure that the breadth of interests, ideas, and values of all people are heard and considered. Outreach and public participation processes will be inclusive of diverse races, cultures, ages, and other social statuses. Effective listening, transparency, flexibility, and adaptability will be utilized to overcome barriers (geography, language, time, design, etc) that prevent or limit participation in public processes.”22 Initiatives such as the One Fairfax resolution are vital for LHAs to promote trust and establish cooperation among racial and ethnic minority communities, non–health sector organizations, and the health system. Research has shown that community engagement in public health improves health outcomes, although there is insufficient evidence to determine whether one particular model of community engagement is more effective than any other.23

In contrast to the perceived strengths of LHAs in combating racism, participants in this study also noted a variety of limitations. In particular, the current scarcity of available staffing and underfunding that plague public health are made evident in the data. Recent downward trends in public health staffing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic have been frequently highlighted by major news outlets.24 Moreover, large-scale analytical reports conducted by Trust for America’s Health have, for years, pointed out the chronic underfunding for public health initiatives, with particular emphasis on the limitations of current government funding to the operational capacity of LHAs.25 Continued advocacy for increased federal public health funding as well as exploration of alternative sources of funding can help LHAs retain their workforce and sustain new initiatives dedicated to health equity.25 As a recent example related to this study, the Anne Arundel County Department of Health in Maryland successfully advocated for the inclusion of a new Office of Health Equity and Racial Justice within the Anne Arundel County Council 2021 fiscal budget, which will provide funding to this office to identify health disparities along racial and ethnic, income, and geographical lines to target for public health intervention.26

The data collected in this study also suggest that lack of control over policy is often a barrier for LHAs to address public health issues with the resources and flexibility that are required. Indeed, it has been hypothesized in the literature that the fragmentation of public health policy development within the US government to the federal, state, and local levels is a considerable issue that fosters a lack of accountability and delays the coordination of responses to public health issues.27 This lack of strategic coordination has been magnified on a national scale by the poor COVID-19 health outcomes in racial and ethnic minority communities and contributes to participants’ adamance in this study to bring policymakers to the table for the discussion of racism and its effect on health. It has been well-established that the power of legislative decision-makers is instrumental in addressing systemic health issues and improving population health outcomes.28 Therefore, the recruitment of diverse, multisector organizations (eg, housing, transportation) that influence policy is necessary to successfully address a national public health issue as deeply rooted as structural racism.

Further, in regard to new strategies operationalized by LHAs to deal with racism, the data most strongly suggest an emphasis on hiring new health equity positions or expanding previously established health equity working groups. Because the constraints of understaffing and funding allocation frequently threaten the sustainability of public health initiatives, the creation of new health equity positions and increased hiring are crucial for this work. Moreover, they are supported by racial equity research, such as the “Protocol for Culturally Responsive Organizations” created by researchers at Portland State University, which describes leadership recruitment and budgetary allocation as critical components of organizational commitment to racial equity.29 The Commonwealth of Virginia Equity Leadership Task Force cited this protocol as a framework for the development of its COVID-19 Health Equity Working Group, which reviews proposed and/or enacted policies related to COVID-19 and determines how vulnerable populations in Virginia may be impacted.30 These interventions represent important progress for DMV legislative bodies to acknowledge and consider racism in the development of future policy that has the potential to influence the health and well-being of racial and ethnic minority communities. While there is little evidence in the literature to demonstrate that hiring more health equity positions directly improves racial health disparities, it is clear that tailored health equity programs designed to reach racial and ethnic minority communities can significantly improve or even eliminate disparities. For example, a cancer control program started by the Delaware Cancer Consortium in 2003 effectively eliminated mortality differences between African American and White individuals in Delaware by 2009.31 While it may be inferred that dedicated hiring and funding contribute to the success of initiatives such as this, further research is necessary to fully elucidate the effectiveness of these strategies.

The addition of racial equity training and inclusivity measures within LHAs was another important strategy described by participants and endorsed by the APHA. The importance of cultural competency training in the educational development of individuals working within the health sector should not be understated—its utility for improving knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health professionals regarding racism, racial health disparities, and social determinants of health is made clear in the literature.32 As we seek to develop a blueprint for dismantling structural racism, a foundational knowledge of these issues through education is necessary to develop antiracist public health officials and health care professionals. However, significant gaps exist in our understanding of the impact of cultural competency training on health outcomes, mainly due to a lack of standardized evaluation tools.33 Future research to address this knowledge deficit is an important next step to address racism as a public health crisis.

This study was qualitative and, as such, is subject to limitations including a small, nonrandom sample of participants and geographic constraints to the Washington, DC/Maryland/Virginia area that limit generalizability to other areas of the United States. Additionally, various structural influences within public health, such as organizational bureaucracy and political interests, have the potential to bias the interview responses, particularly due to the sensitive nature of the topics explored in this study. However, the findings from key informants in this study are consistent with the current body of evidence in the literature and the perspectives of national, state, and local public health organizations. To highlight this consistency, take for example the resolution passed by the Virginia General Assembly to declare racism a public health crisis on February 23, 2021, making it one of the most recent statewide declarations of this nature.34 While this declaration occurred after the period of data collection for this study had concluded, many themes collected from participants working for the Virginia Department of Health align with significant similarity to the 5-objective plan outlined by the declaration.35 This similarity suggests that interview themes collected from key informants in this study may have more external validity than would be expected from a small-scale case series.

Conclusions

Declarations of racism as a public health crisis reflect a shared understanding in public health regarding the influence of racism on disparate health care delivery and medical outcomes. In response to this crisis, LHAs have implemented a variety of strategies in an attempt to improve health equity such as dedicated hiring, forming new positions dedicated to health equity, increasing engagement with racial and ethnic minority communities, enhancing workplace inclusivity training, and continuing to highlight the racial health disparities data for conditions such as COVID-19. Further research is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies; however, racial health disparities are not inevitable and can be eliminated with the appropriate intervention. While the recent shift in rhetoric surrounding racism has been an important catalyst for LHAs to enact structural change for their communities, it is not sufficient to overcome the barriers of inadequate funding, outdated policy, and sparse personnel. Therefore, policymakers, non–health sector partners, and the community are critical to future solutions. Without the engagement of all stakeholders, progress will be slow and incremental and public health organizations will continue to face substantial obstacles in their efforts to dismantle structural racism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank my mentor for this project, Tobie-Lynn Smith, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAFP, whose guidance was instrumental to the initiation and development of this project. I also thank May-Lorie Saint Laurent, who guided me in the early stages of this project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None reported.