Introduction

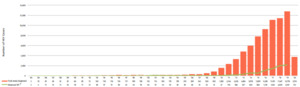

Although having reported low rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence in the Philippines during past decades, HIV infections have increased alarmingly over recent years. Since the very first reported case of HIV in the country in 1984, the rate of infection remained below 0.01% of the entire population until 2007, when infections shifted from majority among heterosexuals to majority among MSM. Since then, in the Philippines the number of infections has increased by more than 500%, as seen in Figure 1, whereby the Philippine government declared the growing epidemic a “national emergency” in August 2017.1,2

Currently the Philippines faces the fastest-growing HIV epidemic in the Asia and Pacific region. Surveillance data of the country shows that of the population, males consistently account for most of the new infections—more than 90%—especially gay men, bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), with almost all infections being transmitted via sexual contact.3 Other modes of infection include sharing needles (~1%) and mother-to-child transmission (<1%).

HIV prevalence rates in the Philippines are higher in younger age groups, namely in the 15-34 age range, and trends predict infection rates to increase in younger ages with time.4 In fact, the Philippine Department of Health reports that the proportion of positive HIV-cases in the 15-24 age group has “nearly doubled in the past ten years, from 17% in 2000 to 2019 to 29% in 2010 to 2019.”1 Sexually active MSM aged 25-29 contribute the most to new HIV infections among MSM in the Philippines, with Ross et al. reporting that “a high proportion of these men are from advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.”5

Despite the growing HIV epidemic in the Philippines among MSM, HIV testing uptake remains low, with de Lind van Wijngaarden et al. reporting only 20% uptake.6 This paper will explore the unique barriers Filipino MSM face in seeking out HIV testing that might save them decades of healthy, worthwhile life. Understanding these factors is key to formulating the most appropriate public health responses by the Philippines government, the key actor in increasing HIV testing to minimize further infections. Our recommendations for necessary government responses could be broadened to other strongly Catholic populations around the world, whose MSM populations report experiencing similar barriers to the ones discussed in this paper that recognize Roman Catholicism as their official religion.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science for the existing literature assessing the epidemiology of the HIV epidemic in the Philippines, any current interventions, and the HIV-testing barriers specific to MSM. We included both research articles and reports released by the Philippine Department of Health written in English and published from 2005 to 2021.

Barriers to HIV Testing in the Philippines

HIV-related stigma in the Philippines. Around the world, HIV-related stigma contributes significantly to increased HIV risk and decreased promotion of HIV care across all populations – not solely MSM.7–9 Individuals living with HIV often experience stigma related to their diagnosis within their own communities, resulting in the development of internalized shame and continued anticipation of discrimination from all areas of their social life, often resulting in adverse health outcomes.9,10 These adverse consequences are the result of various barriers constructed by HIV-related stigma, such as decreased access to testing, increased risk of depression and anxiety, and an increased risk of suicide.11,12 In the Philippines, people living with HIV face a great amount of perceived stigma due to their serostatus, seen as a marker of sin and moral uncleanliness.12 The persistence of HIV-related stigma, most often associated with the strong Catholic roots of the country, contributes to the growing nature of the epidemic, in addition with poor HIV education and low awareness of infection prevention methods.13 MSM living with HIV in the Philippines report facing an additional level of stigma due to their sexuality, found to lead to even more severe psychosocial health problems and reinforcing the aforementioned barriers to seeking out care.12 Some Filipino MSM have reported experiencing a lack of proper treatment from healthcare providers, such as a refusal of treatment by the provider on the grounds of their patients’ HIV/AIDS status.14 Internalization of this societal, dual stigma and the resulting emotional turmoil may contribute to suicidal ideation and self-harmful activities.15

Religious stigma. One held belief of some individuals adhering to Catholic doctrine is that HIV is a disease meant for gay men as a moral reparation for engaging in the sin of homosexual activity.16 Since the Spanish-colonial occupation of the Philippines, Roman Catholicism has maintained its strong presence there, with more than 80% of Filipinos identifying as Roman Catholic, making the Philippines the only predominantly Christian country in all of Asia.17 The Roman Catholic church holds significant influence on the negative perception of MSM living with HIV; in 2006, the Catholic Church opposed a pilot project of sexuality education in two schools in Manila, which would have included HIV education, prompting the Philippine government to scrap the initiative in its entirety.18 Many MSM still adhere to the Roman Catholic tradition, thus finding difficulty and emotional turmoil in accepting their own sexuality and serostatus and the consequences each would have in their “relationship with God.”15

Misconceptions of HIV. Rooted in an innate fear of the virus, misconceptions of its mode of transmission and the consequences after infection have been documented.19 Although most people living in the Philippines know that HIV exists, common misconceptions of the virus itself persist among the general population, health workers included.20 In a 2018 research study exploring the low uptake of HIV testing by gay men in Metro Manila, Philippines, the most pervasive misconceptions found were that healthy physical shape, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and lack of illness related symptoms such as significant loss of body weight meant HIV testing was not needed, despite having an active sex life.6 Most of the study participants also admitted to not seeking out testing due to being “serial monogamists,” meaning they would engage in anal sex without protection in their monogamous relationships, believing that it was safe, despite being in multiple monogamous relationships throughout their life. Some even reported to never knowing their monogamous partner’s HIV status before engaging in sex. Positive Action Foundation Philippines Incorporated reported that many Filipinos have a misconception of the mode of HIV transmission, for example, the virus could be spread through sharing a handshake, getting bitten by a mosquito, or even using the same toilet seat as a person living with HIV.21

Fear of testing positive. De Lind van Wijngaarden et al. also reported one participant who consistently postponed his HIV test, despite having been at risk, in fear of the consequences of a positive result, claiming to be the only HIV-positive within his entire social circle, that he was aware.6 The silent nature of anticipating rejection and social isolation from their own community if tested positive, especially from close family and friends, may result in many MSM untested and remaining at risk.22

Access to testing. Prior to 2018, a legal policy requiring parental consent for HIV testing individuals less than 18 years old greatly discouraged testing among younger and sexually-active Filipino MSM.23 Due to a number of testing center issues, such as lack of sterile testing equipment, long distances from people’s homes, long wait times, and limited hours of operation, MSM living outside populated urban centers lack adequate access to HIV tests.1,6 Additionally, for a country with more than 2000 inhabited islands, the current 104 DOH designated HIV treatment hubs and primary HIV / facilities simply cannot serve adequately every possible at-risk individual. The Philippine government also does not mandate education of effective HIV prevention methods in schools, leaving thousands of MSM unaware of how, when, or why to get tested for HIV.24

Discussion

The current state of the HIV epidemic among MSM in the Philippines cannot be attributed to a single factor. Its persistent and disproportionate effect on MSM is based upon multiple social environmental factors, that discourage seeking testing. However, in 2018, President Duterte signed Republic Act 11166, the renewed Philippine HIV and AIDS Policy Act from 1984, with the hopes to increase accessibility of HIV education, testing, and treatment to all people living with HIV.25 Article II explicitly includes promotion of quality HIV education, the dissemination of accurate information regarding prevention, and the eradication of the pervasive misconceptions of HIV and HIV transmission. The law mandates that all public and private hospitals in the Philippines become HIV treatment hubs and mandates in Section 29 the allowance of minors aged 15 to 17 years old access to voluntary HIV testing without parental consent. Article VII aims to eliminate all discriminatory acts and practices towards people living with HIV on the basis of their serostatus, including discrimination in the workplace, in learning institutions, and in hospitals and other health institutions. With Republic Act 11166 signed, many of its advocates hope for the new programs under this policy to spearhead a growing, national normalization and de-stigmatization of HIV/AIDS. In the past decade, nearby Thailand has found success in combatting these issues, with the Ministry of Public Health, the Thai network of People Living with HIV, and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS having launched a zero discrimination against HIV/AIDS campaign in any and all health-care settings.26 The campaign involved nearly 1000 public hospitals playing videos portraying the realities of living with HIV/AIDS on televisions in waiting rooms to raise awareness about the right of non-discriminatory treatment of people living with HIV/AIDS. The Thai campaign has found such success in combatting HIV stigma and discrimination, that a similar program has been adopted in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam and in Lao PDR, with Myanmar also showing potential interest in doing the same.27

Next Steps

The authors encourage adoption of the following interventions to reduce HIV testing barriers.

-

Sexual health education (safe sex practices and sexually transmitted infection education in addition to HIV education) should be continually integrated into school curriculum and taught by trained teachers.

-

Health care providers should promote HIV awareness via increased explicit exposure to all students in the medical field through required rotations in HIV clinics, via increased implicit exposure in hospital settings (similar to the zero-discrimination campaign in Thailand), and via integration of HIV prevention and treatment services into primary care.

-

Policy makers should consider implementation and regulation of HIV self-testing resources, as self-screening resources have been shown to increase HIV testing uptake among high-risk populations with low access to testing, such as Filipino MSM.23,28

-

Philippine non-governmental organizations (NGOs) ought to work with Roman Catholic churches to urge the necessity of HIV testing to their respective congregations, as HIV education that includes HIV testing held in churches is associated with increased odds of HIV testing afterwards.29

The HIV epidemic in the Philippines is not over, and the underlying causes continue to propel the epidemic—the lack of HIV education, prevention, testing, treatment, care, and support—need to be addressed immediately if the burden of HIV/AIDS in the Philippines is to be eliminated.

Disclaimers

None

Sources of Support

None

Conflicts of Interest

None