On the night of Thursday, September 29, eager football fans across the country geared up for a highly anticipated matchup between 2 offensive powerhouses, the Cincinnati Bengals and the Miami Dolphins. Typically, a Thursday night game involving teams of this caliber would generate enough excitement to capture even a casual sports fan’s attention, but a dark cloud loomed over the National Football League (NFL) in the days leading up to this particular matchup. Only 4 nights prior, Miami’s star quarterback, Tua Tagovailoa, sustained what many speculated was a severe head injury, leaving many to wonder whether he would be cleared to play. The question being asked was simple: Did Tagovailoa have a concussion? Unfortunately, the answer was not as obvious as it might have seemed. While many fans believed his injury to be self-evident, the NFL and the Miami Dolphins believed otherwise. That night, Tua Tagovailoa took to the field.

Disaster struck midway through the second quarter as Tagovailoa faked a handoff and rolled out to his left, looking to pass. With nowhere to throw, he tried to duck away from the oncoming defenders, but time ran out as he was caught in the outstretched arms of a lineman. Charged with momentum, the back of Tagovailoa’s head accelerated as it slammed against the turf like a heavy marble. Suddenly, the tone of the game changed from ominous to treacherous.

Nervous spectators waited to see if the young quarterback would hop back up to his feet. Instead, they were met with stillness: the kind of stillness that immediately signaled something was wrong. As moments passed, the gravity of the situation became clear: Tagovailoa had lost control over his body. He was lying flat on his back with his eyes closed. His arms were extended out in front of his face as if he was blocking the light from a sun that was not in the sky. His fingers revealed the worst; all 10 of them splayed in every direction, seemingly with minds of their own. Players from both teams frantically signaled to the sideline for the medical staff’s attention when they saw his unnatural position, and many of them took off their helmets and kneeled out of respect. The stretcher was rushed onto the field, and Tagovailoa was immediately strapped in. As he was wheeled to the locker room, many fans hoped for some movement: a wave or a thumbs up as many players do to let the crowd know they will soon be alright. But in this moment, Tagovailoa remained still.

After Tagovailoa was loaded into an ambulance and taken to a local hospital, the game went on, but the focus of the night remained on the situation that had just unfolded. A storm of commentary began to brew online as images of the situation spread like wildfire. Social media timelines were flooded with disgust directed at the NFL and the Miami Dolphins. Angry fans called out the organizations for their mishandling of the situation, some even demanding legal action. Andrew Brandt, a writer and sports media insider for ESPN and Sports Illustrated, responded on Twitter by saying, “There are so many reasons Tua [Tagovailoa] shouldn’t have played tonight, and so many people – adults who know better – that allowed it. There will be lawyers.” Current NFL players, including Matthew Judon, a linebacker for the New England Patriots, said online, “[There] was no reason that man should [have] been in the game. SMH. Protect yourself because some people only see you as a football player.” Amongst the commentary, a common theme floated to the surface: When will we put player safety first? This question has been asked too many times before, and it deserves an answer. Unfortunately, with the current state of concussion management in the world, there is no clear direction towards a solution. The need for guidance is stronger now than ever, and it starts with a discussion about the state of concussion research in the medical community.

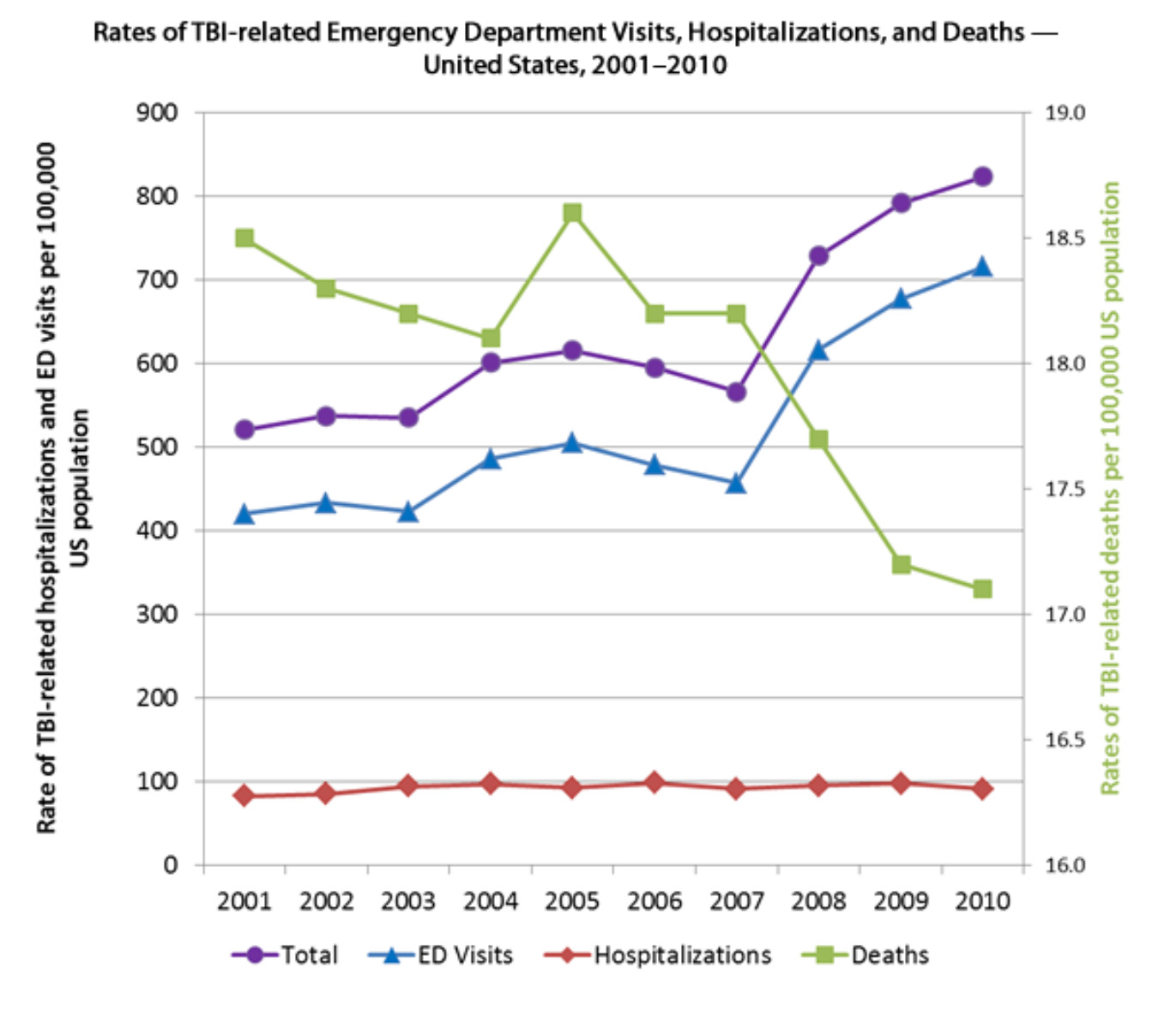

It has been more than 17 years since Bennet Omalu, MD, MBA, MPH, published the first evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in a retired NFL player, Mike Webster, in 2005.1 This study served as the first major warning of the potential lasting impacts of repeated brain trauma in humans. The findings in this article were alarming, and fear began to grow. A new narrative surrounding CTE quickly followed as people became more concerned about head trauma. In 2008, the rates of traumatic brain injury–related emergency department visits drastically increased compared with years prior, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Figure).

Now, instead of telling athletes to “shake it off and get back into the game” after receiving a blow to the head, more people were being brought to the hospital to receive medical attention. As the new narrative developed, it began to outpace the medical community. It was clear to scientists that concussions were dangerous, but far more work needed to be done to support the claims being thrown around because evidence-based research takes significant time to do well. Among these claims was the major concern that concussions cause CTE. One case study, although it carries significant weight, is not enough to form a causal relationship. With billions of eager ears waiting for an answer from the medical community, researchers got to work filling in the gaps.

Fast forward to October 2016, the International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport (ICCCIS) invited leading concussion experts from around the world to Berlin, Germany, to discuss new concussion research. The goal was to develop a consensus statement that would serve as the gold standard for concussion diagnoses and management in sports, and CTE was in the spotlight. Just 1 year prior in 2015, the highly anticipated film “Concussion” starring Will Smith as Omalu reignited the public concern over CTE and the NFL’s attempt to suppress Omalu’s research. The expectation was that the ICCCIS would make an official decision on whether concussions cause CTE and settle the debate once and for all.2 However, this was not the case. In the document published after the meeting, a very short section titled “Residual Effects and Sequelae” stated, “A cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been demonstrated between CTE and sports related concussions (SRCs) or exposure to contact sports. As such, the notion that repeated concussion or sub-concussive impacts cause CTE remains unknown.” The debate raged on, and the tension within the medical community intensified.

Since the release of the last consensus statement, thousands of studies have been published describing a causal link between concussions and CTE.3 The National Institutes of Health, which is the largest funder of brain research in the United States, has stated that CTE is “caused in part by repeated traumatic brain injuries.”4 Despite this growing body of evidence, the ICCCIS still cannot come to an agreement on the causal effect between concussions and CTE. This was evident at the ICCCIS’s most recent conference held in Amsterdam in October 2022 (the first conference held since the initial meeting in 2016). During the discussions, recent studies supporting a causal relationship between concussions and CTE were criticized for lacking proper accountability of confounding variables in their populations by Grant Iverson, PhD, a neuropsychologist at Harvard University who oversaw the session on the long-term impacts of repeated head trauma. Iverson stated in response to these studies, “To think that there is one factor that is contributing to their current problems and that factor you can see under a microscope after death is an extraordinarily naive position when you think about the human condition.”5 After billions of dollars and years of evidence-based research, the medical field had been reduced to opposing groups of believers and deniers.6

Often, the NFL gets blamed for fueling the ambiguity surrounding concussions because of the way it has handled situations in the past. When Tua Tagovailoa went down, the NFL was immediately accused of covering up the truth to allow the star quarterback to play. While the NFL has certainly not been perfect throughout its history, the blame should not be placed entirely on it. The NFL, just like the rest of society, turns to the medical community for guidance and care with issues of human health and safety. Yet, concussion management and prevention are not straightforward issues, and accordingly, how can anyone be expected to make the “right” decisions when experts have not agreed on what those decisions are? We are quick to judge the NFL, but it is stuck in the same limbo as the rest of the country, waiting for the medical community to come to an agreement.

This concern over concussions extends far beyond the NFL to the sports world as a whole. Concussions are a serious issue in many popular sports, and people all over the world are forced to develop ways to diagnose and manage them.7 With an understanding of the current ambiguity surrounding concussions, this begs the question: How should the public deal with this uncertainty? Every day, parents are forced to make difficult decisions about how to raise their children, whether the medical community can provide answers or not. As we develop an approach to this situation, we must set realistic expectations because jumping to any extreme can have severe consequences. For instance, eliminating contact sports altogether is not the right answer.

Sports hold an important place in our society. The physical and mental health benefits of playing sports are evident starting at a young age.8,9 Instead of limiting them, we should encourage sports to be played in a safe and appropriate manner. This starts with taking what we do know about concussions and realistically weigh the risks and benefits. Each day of our lives, we consider the risks of every decision we make. For example, we know that car crashes can be deadly, but we still choose to drive for the convenience of transportation. Playing contact sports is no exception to this rule; we know they can be dangerous, but they are an important part of many people’s lives. Still, we often struggle to decide whether to encourage our loved ones to play them or direct them down other paths. There is no easy answer to this dilemma, which is why it is imperative that we work towards creating a system that can help make this decision easier. Our current way of managing this dilemma is failing us, and we need to take a step back to recalibrate. What we can do is start implementing 3 ideas to help us develop a better approach: accountability, transparency, and action.

One of the first sections of the NFL Head, Neck, and Spine Committee’s Concussion Protocol outlines the importance of educating players on the signs and symptoms of concussions. It encourages them to look out for their teammates and report potential concussions to the medical staff.10 It can be difficult for a player to admit they need help—especially when it may mean missing time from the game they love—but health is more important than the next play, and a team that understands this is one that exemplifies accountability. This starts in the locker room, especially at the top. The NFL and other professional sports leagues set an example for millions of high school athletes. The culture of professional programs trickles down through locker rooms at every level. Stressing player safety at early ages normalizes accountability and facilitates safer playing conditions.

That being said, accountability cannot solely be placed on the players. There are far more people expecting excellence out of players than simply themselves and their teammates. The pressure to play through the pain comes from all directions, including fans. If we tell players to protect themselves and each other, we have to give them the space to do so without judgment or harassment, especially when they enter the concussion protocol. A proper recovery is imperative to ensure that brains heal from a concussion,11 as receiving a second impact without giving the brain enough time to recover can result in serious, lasting consequences.12 Every concussion is different, and every player deserves their own timeline. This is an area where team coaches and executives can take responsibility because encouraging accountability in players does nothing if the ones who make the decisions and write the checks are not held to the same standards. A winning culture extends beyond the players themselves, and respecting players’ lives is far more important than maximizing profits.

Transparency starts with the medical community. We need to do a better job of communicating what we know and, just as importantly, what we do not know about concussions to the general public. Ambiguity breeds controversy, and controversy can destroy credibility and trust. Without trust in the medical community, nobody will listen when we have something important to say. It is alright that we do not always have answers to every question, that is the very nature of science and research. Still, we must remain transparent so people can set realistic expectations. Every mother and father deserve to make an informed decision about their child, and providing that information starts with establishing clarity and trust.

The final point in this game plan is a call to action. Everyone plays a role in creating an environment where future athletes can thrive. Everyone can hold each other more accountable, everyone can be more transparent, and everyone can take a few minutes to learn something new about concussions. After all is said and done, concussions should be just as well understood by everyone as a sprained ankle.

Encouraging someone to play sports should never be frowned on, especially if sports are what inspire them to be active, but the path between encouragement and demand can be dangerous. We have to set limits, and everyone has a responsibility to help decide where we set those limits with respect for player health and safety. With more accountability and transparency, the decision becomes ever easier to make. Only then can athletes feel more comfortable playing the games they love and their supporters feel more confident in their futures both on and off the field.

Special thank you to Dr. Mark Burns, Ph.D. for allowing me to interview him on the topic.