Introduction

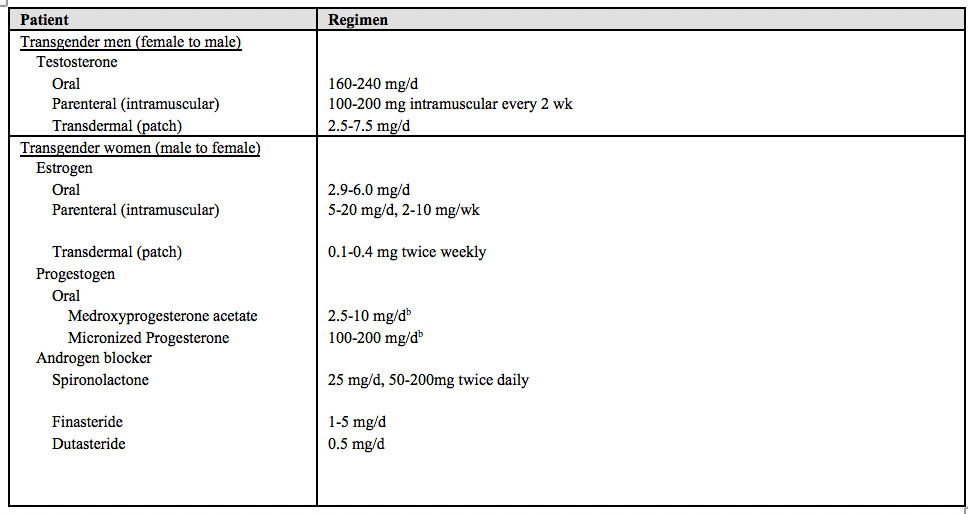

Transgender individuals have a gender identity that differs from their birth sex (Table 1). Gender affirmation is conceptualized as having 4 facets. These are social (ie, pronoun), psychological, medical, and legal.1 Gender-affirming medical therapies help these individuals transition to the gender that they identify with through combinations of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and sexual reassignment surgery (SRS). HRT involves the chronic administration of exogenous sex hormones in patients transitioning from female to male (FtM) or male to female (MtF) in order to suppress the sexual characteristics and hormones of a person’s birth sex and to encourage the development of those that correspond with the patient’s gender identity (Table 2).2 An emerging concern among clinicians is the impact of the long-term administration of hormones on disease, particularly cancer.3 The dearth of current epidemiological data about the risk of gender-affirming HRT and breast cancer demonstrates a recognized gap in clinical knowledge. This review outlines the biological roles of the hormones used in gender-affirming therapy (testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone) and provides an overview of existing data that are relevant to understanding the risks of this therapy in regard to breast cancer. Elucidating the disparities in care that many transgender patients experience can ultimately improve the quality of care for these patient populations. Given the potential risks of HRT and these disparities, it is pertinent to suggest an approach to the screening of transgender patients for breast cancer that is feasible and effective for physicians in the clinic. Based on what is known, the long-term effects of HRT in these patients require further investigation.

aInformation in this table was adapted from Sonnenblick et al.4

aData compiled from Hembree et al2 and Deutsch et al.5

bGenerally given at night.

Role of HRT in Breast Cancer

Testosterone

Testosterone is a steroid hormone produced in both males and females. The gonads and, to a lesser extent, the adrenals produce testosterone in males and females, which is a primary ligand of the androgen receptor (AR).6 In males, testosterone promotes sexual development and the maturation of secondary sexual characteristics, including hair growth and increased muscle mass.7 In females, the enzyme aromatase can convert testosterone into estrogen, or testosterone can bind to ARs where it suppresses breast growth, among other functions.7 The antiproliferative effects of testosterone on mammary epithelia contribute to its use in treating some forms of breast cancer, whereas promoting virility underlies its use in transgender men who undergo HRT.6,8

Estrogen and Progesterone

In the female reproductive system, estrogen is the dominant regulatory sex hormone. It acts at receptors in multiple body tissues, particularly in reproductive organs. It is also the primary hormone used in MtF transition therapy.9

Activation of the estrogen receptor (ER) has been found to be associated with cell proliferation, metastasis, and invasion in breast cancer.10 Estrogen administration in animal models has also led to development of mammary tumors.10 This is the rationale behind ER antagonists, such as tamoxifen, which block the ER and reduce endogenous estrogen levels in patients with receptor-positive breast cancers.9

While much of the therapeutic focus in breast cancers is on the role of estrogen, the sex hormone progesterone also plays an important role in HRT for MtF transgender patients. In mouse models, progesterone acts on tissue receptors to activate the expansion of mammary stem cells, which suggests that progesterone affects mammary gland proliferation in adults.11

Exogenous Estrogen/Progesterone Therapy: Summary of Existing Literature

The studies discussed here have investigated the long-term administration of exogenous estrogens and progesterones and have focused on HRT in postmenopausal women. There is justification for considering this research here because it provides evidence for the effects of long- term administration of exogenous progesterones and estrogens on breast carcinogenesis.

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomly assigned 16,608 participants (postmenopausal women) to either an active treatment or placebo group. The active treatment group received conjugated equine estrogens (0.625 mg/day) in conjunction with medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/day). The mean intervention time was 5.6 years, and the mean follow-up time was 7.9 years. The study authors found a slightly increased incidence of breast cancer (hazard ratio, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.07-1.46]; p = .004) with estrogen/progesterone combination HRT compared with placebo.12

In the Million Women Study (MWS), 1,084,110 UK women recruited between 1996 and 2001 provided information regarding their use of HRT. Subsequent follow-up examined the incidence of breast cancer and death. This study found a significantly increased incidence (RR=1.66 [95% CI, 1.58-1.75]; p < .001) of breast cancer in women using HRT at the time of recruitment. This increased incidence occurred with both estrogen-only HRT (RR=1.30 [95% CI, 1.21-1.40]; p < .001) as well as estrogen/progesterone HRT (RR=2.0 [95% CI, 1.88-2.12]; p < .001). Notably, breast cancer risk was associated with total duration of HRT use.13

A subsequent trial of 17,437 separate participants in the WHI cohort found no evidence of increased risk of breast cancer with estrogen-only HRT (conjugated equine estrogen, 0.625 mg/day) compared with placebo.14 This finding contrasts with the results of the MWS. However, this trial was halted after an increased risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism in the group receiving estrogen, which reduced follow-up to a median of 5 years compared with 7.9 years in the estrogen/progesterone combination study.10 Regardless, the increased risk with estrogen/progesterone combination therapy appears consistent.

Further supporting the results of the WHI and MWS, decreases in breast cancer incidence have been observed at the population level in correlation with decreased prescription and use of HRT. In Australia, where prescribing of HRT declined 40% between 2001 and 2003 (following publication of the first results of the WHI), breast cancer incidence in women older than age 50 years declined by 6.7%.15 Noting no similar decreased incidence in women younger than 50, the authors suggested these results were consistent with HRT being a significant risk factor for breast cancer.15

Finally, the extended use of estrogen/progesterone oral contraceptives as well as progesterone-only intrauterine systems has been recently associated with a slight increased risk of breast cancer (RR=1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).16 This is still an emerging topic of investigation, but the most recent evidence is based on a study of 1.8 million women in Denmark aged 15 to 49 years, with an average follow-up time of 10.9 years.16 Importantly, the authors also found that breast cancer risk was increased with longer duration of use (RR=1.09 [95% CI, 0.96-1.23] with less than 1 year of use and 1.38 [95% CI, 1.26-1.51] with more than 10 years of use; p = .002).

HRT in FtM transition

Testosterone is used in transgender men to induce hair growth, enhance muscle mass, deepen the voice, and suppress menstruation.8 Patients typically receive parenteral or transdermal doses of testosterone prepared to achieve levels consistent with those found in most biological males (320-1000 ng/dL) (Table 2).2 Some patients may receive a combination of testosterone and an aromatase inhibitor to prevent the excessive conversion of testosterone into estrogen.17 A nonexhaustive list of indications for the use of combination therapy include patients with elevated estrogen, fluid retention or bloating, abnormal uterine bleeding, obesity, and a history of or increased risk of developing breast cancer.17 In addition to HRT, about one-quarter of transgender patients undergo SRS.18 For transgender men, SRS may include bilateral mastectomy, hysterectomy and oophorectomy, and/or phalloplasty.2,18 Although HRT is the focus of this review, it is important to consider what role SRS may play in the development or prevention of breast cancer.

Multiple studies have attempted to elucidate a relationship between testosterone and breast cancer risk. Although there is not yet a consensus,19,20 a growing body of literature suggests that the administration of exogenous testosterone either has no effect or may reduce breast cancer risk in biological females.6,8,21,22 Most of these studies have assessed testosterone’s relationship to breast cancer in biologically female patients regardless of their gender identity. Fewer studies have explored breast cancer risk in transgender men undergoing testosterone HRT.

HRT in MtF transition

Given the evidence suggesting an association with breast cancer, the concern of clinicians treating MtF patients with long-term administration of exogenous estrogens and progesterones is understandable. Of primary concern is the potential carcinogenic effect of progesterones, which have been consistently linked to an increased incidence of breast cancer in population-based studies such as those discussed here. While estrogen’s role in carcinogenesis is more widely debated, long-term administration of exogenous estrogen should also be viewed as a potential risk factor for receptor-positive cancers because pharmacologically blocking estrogen and its receptor (ER) is therapeutic in patients with receptor-positive breast cancer9 and there is a lack of long term-follow-up studies investigating estrogen’s effects as monotherapy in HRT.

Transgender Breast Cancer Cases

Overview

Breast cancer cases have been reported in transgender patients but there is a dearth of literature and analysis. There remains a knowledge gap in assessment, incidence, and risk of breast cancer in transgender patients. Braun et al23 conducted a comprehensive review of the present literature of cancer in transgender patients; after assessing 28 case reports, 5 epidemiological studies, and 1 article that included both, they identified 15 MtF and 7 FtM transgender breast cancer cases.24–28 Reported patient location, age, demographics, and cancer details of these cases are shown in Table 3. Reporting on breast cancer receptor subtypes, as outlined in Table 3, supports the need to acknowledge a possible association between breast cancer in transgender patients and HRT (testosterone or estrogen and progesterone).23 This need is enforced by the previously discussed evidence showing that the long-term administration of exogenous sex hormones, estrogen in particular, may play a role in breast carcinogenesis.

aInformation in the table was adapted from Braun et al,23 Gooren et al,24 Gooren et al,25 Nikolic et al,26 Shao et al,27 and Burcombe et al.28

bBRCA1 and BRAC2 are breast cancer susceptibility genes.

Testosterone and Breast Cancer: Incidence and Cases

Wierckx et al8 conducted a survey of 50 Dutch transgender men who underwent SRS (including mastectomy and oophorectomy) and received testosterone therapy for an average of 10 years (range, 2-28 years). No cases of hormone-related cancer were found in this population.8 Gooren et al25 followed up a larger Dutch cohort of 795 transgender men (Table 3) who used testosterone for a mean (SD) of 20.1 (7.3) years (range, 6.0-36 years) and found a breast cancer incidence rate of 5.9 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI, 0.5-27.4).25 This is similar to the incidence of 1.1 per 100,000 person-years observed in biologic males compared with the expected 154.7 per 100,000 person-years for all biologic females.25

Brown et al3 analyzed breast cancer in 5,135 transgender patients (irrespective of HRT) within the US Veterans Health Administration system (Table 4). In the cohort of FtM transgender patients, there were 3 cases of breast cancer, with a standard incidence ratio (gold standard for evaluating cancer incidence) of 33.3 (95% CI, 21.9-45.2).3 This suggests there is no elevated risk of breast cancer among FtM transgender patients.

Patients in the studies discussed here tended to initiate HRT at a relatively young age (mean [SD], 23.2 [6.5] years), which limits the applicability of these results to patients that begin HRT at an advanced age.25 There do not appear to be any comprehensive studies that address the risks of initiating HRT in elderly transgender men. What we know is based largely on conjecture from the use of HRT in elderly heterosexual males and females.29 These results, however, have not shown a significant increased risk of breast cancer in elderly men starting testosterone therapy for the first time or in those who underwent long-term treatment to maintain normal physiological levels of testosterone.29 Therefore, patient age for elderly transgender men starting testosterone therapy may not constitute a large risk factor for developing breast cancer; however, further research is needed.

aData compiled from Gooren et al,25 Brown et al 20153 and 2016,30 and Braun et al.23

bIncidence calculated from 2 cases of breast cancer divided by a total of 49,370 person-years of follow-up. Gooren et al25 reported a 95% CI of 0.8 to 13.0 per 100,000 person-years.

cIncidence calculated from 1 case of breast cancer divided by a total of 17,025 person-years of follow-up. Gooren et al25 reported a 95% CI of 0.5 to 27.4 per 100,000 person-years.

Estrogen and Breast Cancer: Incidence and Cases

Two large published studies estimated MtF transgender breast cancer incidence. Gooren et al25 assessed breast cancer in 2,307 MtF transgender patients at Free University Hospital in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (Table 4). The breast cancer incidence among transgender women was higher than in nontransgender-born males (4.1 [95% CI, 0.8-13] compared with 1.2 per 100,000 person-years), which did not reach statistical significance. This suggests there was no elevated breast cancer risk among transgender women.25

Within the Veterans Health Administration cohort of 5,135 transgender patients, Brown et al3 identified 7 cases of breast cancer within MtF transgender patients, with a standard incidence ratio of 77.8 (95% CI, 59.0-94.0). This again suggests a lower breast cancer incidence among MtF transgender patients compared with the general population.

Study Limitations

The major limitations of these studies include duration, epidemiological data quality, and sample size to adequately assess cancer risk.3,23,25 Even the large US veteran study including 5,135 patients may lack sufficient power to adequately predict breast cancer incidence. Additionally, each of the transgender patients was categorized as male or female in the electronic medical record and no data exist on whether this characterization was at birth or was the current gender identity, which represents the largest flaw in this study. Controlling for HRT or gender-reassignment surgery may alter study results. Finally, Brown et al3 reported a rate of overall observed vs expected confirmed breast cancer cases of 1.36 per 100,000 (95% CI, 0.03-5.57). Because this confidence interval crosses 1, the incidence of breast cancer in the entire cohort of transgender patients is not statistically significant compared with the general population.3 However, this combined comparison might miss more nuanced impacts of HRT on breast cancer in transgender patients.

Notably, there is no randomized clinical trial data available. Furthermore, there are several limitations that prevent generalizing the results of testosterone HRT within the general male population for transgender men, for example, few studies looked exclusively at HRT without SRS, which may pose an uncertain link between testosterone and cancer.8,25 The presence or absence of breast tissue is a key variable to consider in cancer development, and transgender men without SRS taking HRT might inflate the impact of testosterone on breast cancer. This variable might also compound results in studies of transgender women who undergo HRT.31 More studies overcoming these barriers are needed.

Screening Recommendations

While further exploration is needed to link HRT to the development of certain cancers, there is evidence that suggests there are disparities in cancer screening for transgender patients. There is a significant deficit in overall cancer screening for transgender patients. The current system lacks patient sensitivity, education for both clinician and patient, and most importantly, a shared decision-making model for providing cancer screening for transgender patients. This deficit ultimately places transgender patient populations at greater risk of developing high-grade cancerous malignancies, regardless of the effects of HRT.

In a study of 220 patients aged 40 to 74 years, Narayan et al32 found that transgender and nontransgender patients were equally as likely to undergo mammography, regardless of income category, higher education category, and health insurance. However, it should not be assumed that the younger generation of transgender patients would have equal levels of adherence to doctor’s visits and recommendations. In addition, a study of more than 2,000 transgender men, women, and gender-nonconforming (GNC) patients aged 18 to older than 65 suggested transgender patients may avoid certain screenings that conflict with their current gender. For example, a transgender man might be resistant to the suggestion to undergo a mammogram.33 This leads to the importance of clinician sensitivity towards transgender patients, especially when discussing cancer screening. Compassionate and sensitive treatment begins as soon as the patient walks in the door, starting with intake forms that allow a patient to self-identify gender, preferred name, and pronoun. Gender-neutral bathrooms and private changing rooms can provide further comfort to a transgender patient. These acts of sensitivity can lead to greater physician-patient rapport as well as patient adherence.4

In the event that patients do seek proper care, clinicians may not know to screen based on a patient’s anatomy, rather than solely their gender. A clinician must provide a mammogram for a patient of any gender who exhibits significant breast tissue, regardless of the patient’s current gender. This highlights the first potential gap in clinician understanding when providing cancer screening to transgender patients.33

Tabaac et al33 found significant screening disparities in transgender patients for more than just mammograms. Transgender women experienced lower rates of up-to-date colorectal cancer screening. Transgender women and transgender men saw fewer lifetime prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests. Of note, transwomen exhibited lower rates of discussing the advantages and disadvantages of PSA tests with their health care providers. It is imperative that clinicians remember to communicate the utility of such screening tests with their patients, especially in the sensitive case of a transgender patient. Such discussion could decrease the likelihood that a patient is lost to follow-up. This communication pitfall presents a second potential deficit in clinician understanding when providing cancer screening to transgender patients.33

Deutsch et al5 recommended the use of a shared decision-making model to aid clinicians in navigating breast cancer screening for transgender patient populations. Numerous studies provide recommendations for which patients should undergo screening and when, as well as the ideal screening modality.4,5,34 However, to our knowledge, no previous studies that compiled current breast cancer screening recommendations for all relevant patient populations in a single decision-making model. Furthermore, as Maglione et al34 described, there is a lack of definitive data generated by randomized clinical trials to identify the best screening practices for this patient population. Until that data are collected, Maglione et al34 and Deutsch et al5 recommend adherence to the recommendations put forth by the American Cancer Society, Endocrine Society and others that treat these patient populations.

The current breast cancer screening recommendations for transgender men, transgender women, cis female, and cis male populations are shown in Figure 1. For completeness and comparison, these recommendations include all relevant populations rather than only transgender populations. Deutsch et al5 outlined specific recommendations for screening mammography in transgender women based on age and length of HRT use, which were supported by a study conducted by Moss et al.35 Deutsch et al5 referenced additional recommendations based on previously conducted studies for the frequency of screening as well as patients with soft-tissue breast fillers.36,37 In the case of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations, clinicians should provide additional genetic counseling referrals for patients. This recommendation furthers patient education and provides an additional element of sensitivity after what can often be an unexpected test result.5 Additional recommendations are provided for patients with Klinefelter syndrome.38 The recommendations summarized in Figure 1 are not evidence based; for this reason, if evaluated and assigned a rating by the US Preventive Services Task Force, these screening recommendations would most likely receive an “I” rating at this time, indicating insufficient evidence. However, these recommendations are based on currently accepted best practices by the professional physician societies that treat these patient populations.5 These recommendations would provide a strong foundation for future randomized clinical trials to provide evidence-based screening guidelines in these patient populations.

Using the information outlined in Figure 1, along with instituting the aforementioned recommendations for creating a compassionate, sensitive health care environment, would allow clinicians to provide a safe space for transgender patients. Creating a safe health care environment will strengthen the patient-physician relationship, encourage patient adherence, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Screening Recommendations for GNC Patients

Tabaac et al33 found that GNC patients avoid screening procedures that will conflict with how they see their own bodies. In the study, GNC patients underwent fewer lifetime PSA tests, fewer colorectal cancer screenings, and fewer mammograms. The authors emphasized that proper patient communication could be a key strategy in addressing this disparity.

Of note, Figure 1 does not explicitly dictate recommendations for GNC individuals. The studies referenced also did not explicitly make these recommendations. Instead, recommendations for GNC individuals should consider anatomy, age, years taking HRT, genetic factors, family history, and any additional major risk factors.4,5,34

Conclusion

Both patients and clinicians should be cognizant of the association between HRT and breast cancer. This is of note given HRT’s potential association with receptor-positive breast cancers, which are the most commonly observed type in male cases. Additional larger-scale, robust, adequately powered studies are warranted to elucidate and quantify the risk of breast cancer in both FtM and MtF transgender patients. Communicating these risks to a patient, ideally prior to the start of a gender transition, is imperative for patient autonomy, personal health awareness, and alignment of patient and provider health care expectations.

The importance of proper clinician education regarding the relationship between HRT and the development of breast cancer as well as the appropriate cancer screening modalities for transgender patients cannot be underestimated. While the relationship between HRT and breast cancer development needs further elucidation, the current literature, as discussed in this review, supports the level of screening recommended in Figure 1.

The following 3-pronged approach for cancer screening in transgender populations is recommended to promote optimal care. First, the clinician must be properly informed of the risks of HRT and the cancer screening standards for each patient. Clinicians may use the information outlined in Figure 1 as a tool for education and quick reference regarding cancer screening standards. Second, the clinician must maintain clear communication of potential cancer risks associated with HRT specific to that patient. Third, a clinician must maintain proper competency and sensitivity in these patient interactions. Maintaining competency begins as soon as a patient enters a clinic and continues throughout a patient interaction. Transgender patients faced with discussions of cancer risk, screening, and especially diagnosis can experience a wide range of emotions, which a clinician must appreciate.

It is important for clinicians to recognize that health care disparities in transgender patient populations stem from more than sociodemographic factors. Health-related surveillance must take care to properly inform clinicians and policy makers of up-to-date cancer screening guidelines. Robust clinician education, competent patient-clinician communication, and proper patient sensitivity can ensure that the transgender patient population is not left vulnerable to high-grade malignancies.