Introduction:

Primary pulmonary sarcomas are mesenchymal-type tumors that typically originate in the lung parenchyma (70%), bronchial wall (20%), or pulmonary artery (10%). These tumors are extremely rare; as of 2006,1 there were approximately 300 cases described in the literature, and they account for only 0.2% to 0.5% of all primary lung malignancies. Primary pulmonary leiomyosarcomas (PPLs) are unlikely to metastasize, but often do so late in the course of disease progression.2 They often raise a diagnostic dilemma; of the literature reviewed, a definitive diagnosis was made before surgery in only 37% of cases.3 Because PPLs rarely exfoliate, histological examination of tissue samples remains the standard for diagnosis of PPL. Here we describe a rare case of the endobronchial form of PPL in a patient who presented with sepsis due to postobstructive pneumonia.

Materials and Methods

An Ovid MEDLINE search using the term pulmonary leiomyosarcoma was used to gather case reports and review articles. A clinical case is presented and the literature reviewed with a focus on the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary leiomyosarcomas.

Case Presentation

The patient was a 40-year-old white woman with a medical history significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, and Down syndrome and who presented with dyspnea and fevers up to 102°F. She had recently completed an outpatient course of azithromycin, but she presented to an outside hospital for worsening shortness of breath despite this therapy. At the outside hospital, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed a 3.7-cm heterogeneously enhancing mass that obstructed the bronchus intermedius with right middle and lower lobe consolidation (Figure 1a). The coronal thoracic CT scan demonstrated right middle and lower lobes that were atelectatic and consolidated with extensive and diffuse secondary mucous plugging (Figure 1b). Laboratory examination results at this time were significant for a white blood cell count 16.5x103/µL, sodium level of 133 mEq/L, potassium level of 3.2 mEq/L, serum creatinine level of 0.54 mg/dL, calcium level of 11.7 mg/dL, and lactic acid level of 2 mmol/L. She was transferred to the presenting institution for further evaluation and management.

Pertinent physical examination findings are shown in the Table.

The patient was diagnosed as having severe sepsis due to postobstructive pneumonia. Treatment with empiric vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam was started, and blood cultures drawn at the outside hospital later returned positive for growth of Haemophilus influenzae. Due to increasing hypoxia and hemodynamic instability (mean arterial pressure <60 mm Hg), she was transferred to the medical intensive care unit for further treatment.

While in intensive care, bronchoscopy revealed a mass nearly obstructing the bronchus intermedius (Figure 2) and a second mass between the left upper lobe and the lingula. Initially, endoscopic fine-needle aspiration and bronchoalveolar lavage were negative for evidence of malignancy. The patient subsequently underwent endobronchial ultrasonography and transbronchial needle biopsy of the mediastinal lymph nodes. The left-sided lesion was removed, but debulking was unsuccessful at opening the bronchus intermedius. Pathology of tissue taken demonstrated both endobronchial lesions to be low-grade mesenchymal neoplasms with smooth muscle differentiation, consistent with leiomyosarcoma. To rule out metastasis, a positron emission tomography scan was performed and demonstrated an absence of metastatic foci.

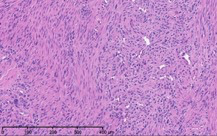

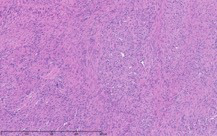

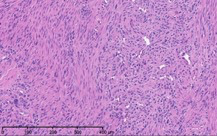

As part of the patient’s treatment, the thoracic surgery team performed a right middle and lower lobectomy. A 4-cm mass in the right bronchus intermedius without invasion into the lung parenchyma was revealed, and pathology confirmed the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. The sections of pulmonary tissue from the right middle and lower lobectomy showed a spindle cell tumor most consistent with leiomyosarcoma (Figure 3a-d). Most of the tumor was low grade, with some foci showing high-grade nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity. Despite these rare mitotic figures, there was no evidence of necrosis. Following surgery, chemotherapy was planned for the patient. However, the patient’s postoperative course was complicated by persistent hypoxic respiratory failure, hypovolemic and hemorrhagic shock, and acute kidney injury. Her respiratory status continued to decline, and she went into cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity. She was resuscitated; however, her shock and respiratory failure worsened despite aggressive therapy. Her family chose to transition her to comfort care, and the patient died.

Background

Primary pulmonary sarcomas are extremely rare. These sarcomas are most frequently leiomyosarcomas, followed by fibrosarcomas and hemangiopericytomas.4 They occur most often in individuals older than 50 years, and they affect males at twice the rate of females. In one study, 83% of cases were found to involve white individuals.5

The endobronchial form of PPL in particular is exceptionally rare, as only 14 patients older than 20 years of age have thus far been reported.3 Of reviewed literature, a definitive diagnosis was made before surgery in only 37% of cases.3

Diagnosis

PPLs are difficult to diagnose.6 They tend to expand locally in the lung parenchyma and thus mimic more common nonsarcomatous tumors in their clinical and macroscopic presentation in addition to their appearance on radiographic imaging.6 They do, however, have a tendency to rapidly expand.2 Plain films of the chest typically demonstrate a well-circumscribed, smooth, or lobulated round mass. A CT scan can be helpful to demonstrate local extension2 and rule out a primary chest wall tumor that has extended into thoracic structures.2 On CT imaging, PPLs are usually solitary, smooth, round, heterogeneous densities with areas of calcification identifying ischemic necrosis.2 Leiomyosarcomas additionally have a propensity to be located in the upper lobes of the lung. If a tumor is discovered in this region in a patient free from significant exposure to tobacco smoke, the possibility of a leiomyosarcoma becomes more distinct.1 In making the diagnosis of PPL, it is important to first rule out the possibility of a secondary source of the neoplasm, especially considering that extrapulmonary sarcoma metastases are more common than tumors of primary origin.6

Histological examination of tissue samples remains the standard for diagnosing PPLs,5 especially considering the difficulty of obtaining useful data from other modalities. Leiomyosarcomas typically travel through the bloodstream and occasionally the lymphatics, and they rarely exfoliate. This behavior makes it unlikely to obtain meaningful samples from bronchoscopy and washings/brushings, and mediastinoscopy is not useful in making a definitive diagnosis because leiomyosarcomas typically metastasize via the blood or lymph.6 Pleural fluid samples also provide little value in the diagnostic process.6

The use of immunohistochemistry staining can also augment the process of diagnosis and classification of sarcomas. For leiomyosarcomas in particular, staining is positive for vimentin,5 desmin,5 and actin1 in approximately 60% of patients with this neoplasm. If staining were to return positive for expression of vimentin and S100 protein, these results would point more strongly toward a diagnosis of melanoma.1 Immunohistochemistry also can help distinguish the grade of the sarcoma. Low-grade leiomyosarcomas are more often associated with positive muscle markers, including smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmone. On the other hand, high-grade tumors are more likely to be negative for these muscle markers. Finally, it is possible that classification may be confused for carcinosarcoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, a tumor that would likely show immunoreactivity to cytokeratin staining. As a result, epithelial markers can be added to the staining protocol to ensure proper diagnosis.3

Treatment/Prognosis

Surgery is the preferred treatment if there is no evidence of metastatic spread in preoperative staging.5 Lobectomy and pneumonectomy, if performed early, can lead to 5-year survival rates of more than 50%, and some patients have survived 20 years after resection.5 Complete resection of the entire mass is recommended if the patient is capable of undergoing aggressive surgery to take advantage of these increased survival rates.1 Radiotherapy can be included in the treatment regimen if surgery is contraindicated or if complete resection is not possible, and it is best suited for local control of tumor extension.1 Radiotherapy, though, has not been correlated with increased survival.5 Chemotherapy, usually in the form of doxorubicin and ifosfamide, are most often reserved for more advanced or metastatic leiomyosarcomas and have been shown to reduce tumor size in less than 20% of cases.1 Adriamycin regimens have achieved a tumor response in 16% to 27% of cases.3

In a cohort study, cancer-directed surgery was performed on 60.4% of patients, while 14.1% received radiotherapy.5 The median overall survival was 14 months with 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival of 52.7%, 29.0%, and 22.2%, respectively.5 Surgery extended the median overall survival by nearly 29 months, and it lowered the risk of death by 57%.5

Tumor size does not necessarily correlate to prognosis of the disease. The grade and differentiation of the tumor are more reliable markers, with low-grade neoplasms developing more slowly.3 One study found correlation between PPL survival and factors including tumor differentiation, primary location, stage, involvement of lymph nodes, and presence of metastases. These factors, however, were not positively associated with PPL survival after adjusting for certain variables.5

Conclusion

Bilateral endobronchial PPLs, as seen in this case, are extremely rare. Most case reports of PPLs demonstrate unilateral masses, and 70% of PPLs occur in the parenchyma compared with only 20% in the bronchial tree. In addition, considering that only 37% of endobronchial leiomyosarcomas were diagnosed preoperatively in the cohort study, definitive diagnosis of this tumor presentation was extraordinarily unusual.3 Furthermore, while this patient did fit the trend of primary pulmonary sarcomas’ tendency in affecting white individuals, she fell outside of the disease’s typical demographics considering her age and sex.

This patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan to rule out the presence of secondary, metastatic disease. Her diagnosis was made with the gold standard of histological examination, using tissue taken from bronchoscopy and subsequent lobectomy. In addition, as predicted given leiomyosarcoma’s tendency to exfoliate poorly, her bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for evidence of malignancy.

The immunohistochemistry staining also lent additional support to the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma. As would be expected for such a diagnosis, both vimentin and desmin were immunoreactive. The tissue also stained positive for muscle markers including smooth-muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and desmin, thus supporting the histological diagnosis of low-grade (highly differentiated) leiomyosarcoma. The tissue stained negative for S100, therefore pointing away from melanoma as a potential diagnosis. The immunohistochemistry profile also included pankeratin staining to distinguish a potential carcinosarcoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, and this test result returned negative.

The patient’s malignancy followed the typical behavior of endobronchial leiomyosarcoma. These tumors are expected to expand locally, although there was no evidence that her tumors had yet reached this stage of invasion. After lobectomy, surgical pathology of the mass obstructing the bronchus intermedius demonstrated that the tumor had not invaded the visceral pleura, nor were there positive margins at the bronchial, vascular, or parenchymal margins. The tumor was 1 cm from the closest margin. Also in alignment with the diagnosis of a low-grade leiomyosarcoma, there was no evidence of malignant spread to any of the 4 lymph nodes histologically examined, and Ki-67 staining highlighted less than 5% of cell nuclei in the right lung mass and less than 1% of cell nuclei in the left lung mass. Her tumor staging was pT3 pN0.

The patient’s comorbidities of asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, and Down syndrome make it difficult to compare her treatment and prognosis to others with the same disease, but they simultaneously make her case unique. Her genetic disability could have led to airway anomalies (as potentially evidenced by her asthma and obstructive sleep apnea) or other complications that would have prohibited a longer survival despite treatment. In line with common guidelines for patients without metastases, she received a bilobectomy. She survived for only 1 week after her surgery, but she was already in unstable condition considering her respiratory failure and significant metabolic imbalances.

This case offers an examination of a condition of extraordinary rarity. Not only was the neoplasm confirmed to be a primary pulmonary leiomyosarcoma, but it was also endobronchial in origin, bilateral, and diagnosed preoperatively. The patient’s age and sex were also in contrast to the typical patient population of primary pulmonary sarcomas. Each of these characteristics are unusual separately, and together compose a unique case. Consent for the writing and use of images for this case report was provided by the deceased patient’s family member.

Disclaimers: none