Introduction

On Yom Kippur, the 10th day of the Jewish month of Tishrei, Jewish people around the world fast for 25 hours, abstain from creative work, and atone for past wrongs. It is a ritual that has been practiced for thousands of years, dating back to the time before the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of the Jewish people from the land of Israel. Yom Kippur is considered the holiest day of the Jewish calendar.

Yom Kippur, Hebrew for “Day of Atonement,” offers a cherished opportunity to reconnect spiritually above the needs of the material world. Many Jewish people who do not celebrate any other holidays continue to celebrate Yom Kippur. Culturally speaking, fasting is a critical and defining aspect of the holiday. However, Jewish people are not permitted to fast if their health is at stake. Medical experts, both Jewish and non-Jewish, play an important role in determining whether fasting is acceptable. It is important that physicians with Jewish patients recognize the role they play for their patients on Yom Kippur and the medical literature regarding contraindications to fasting for 25 hours.

Halakha of the Yom Kippur Fast

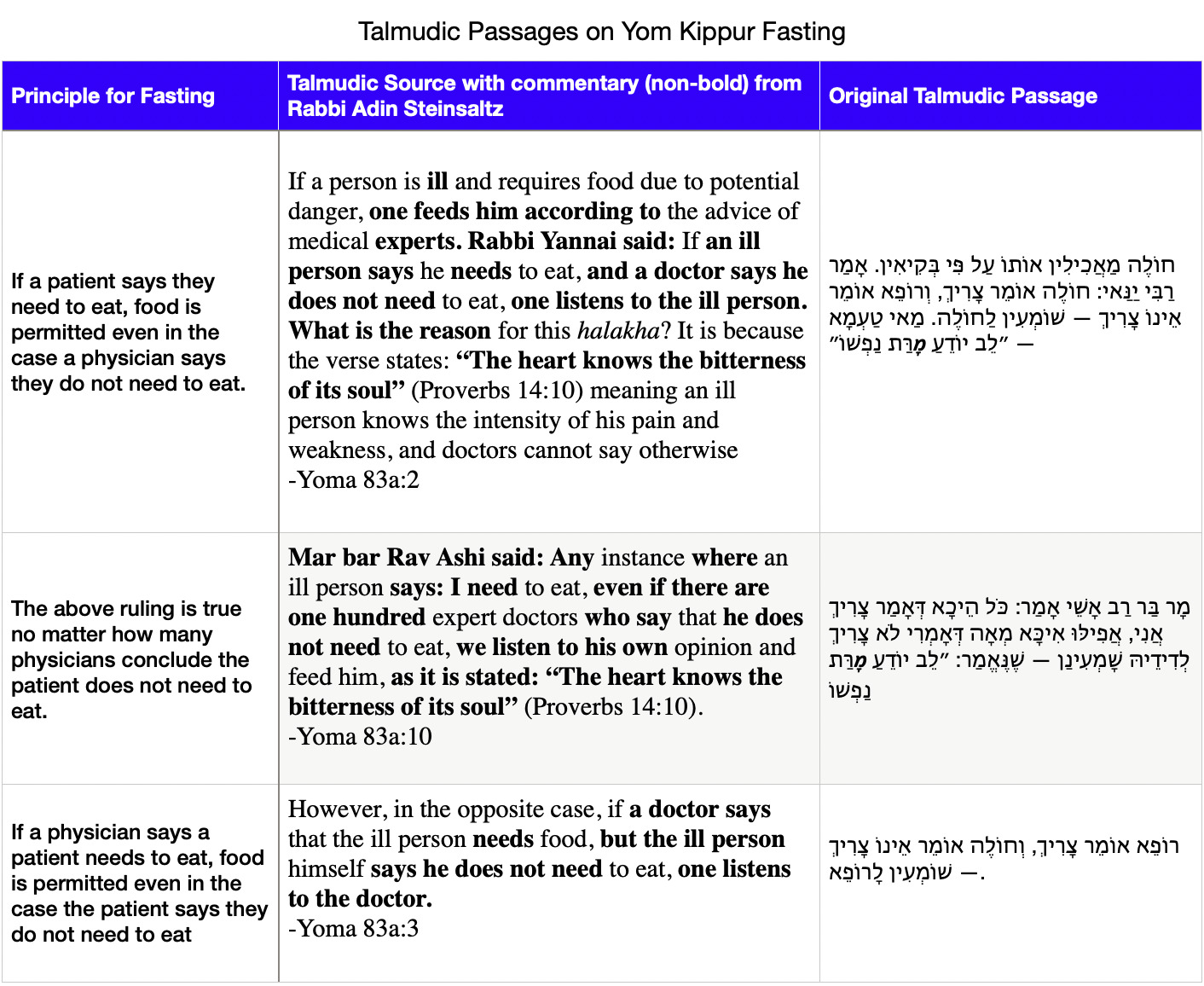

Material restriction is an important aspect of celebrating Yom Kippur. Halakha, Jewish law, requires abstaining from eating and drinking, using oils and fragrances, wearing leather shoes, and engaging in marital relations. However, Jewish law allows for great leniency regarding the fast if health is at stake. If either the patient or physician decides they require food, eating is allowed, even in the case that they disagree. The Talmud, the authoritative work of oral Jewish law compiled by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi in the 2nd century ce, states these laws (Table 1).1

These laws illuminate the nature of fasting on Yom Kippur as well. Rather than self-flagellation for past transgressions where more suffering is better, fasting is meant to remind oneself of the fleeting nature of the material world and the fundamentally spiritual nature of life. One cannot participate in this level of reflection if their illness is exacerbated by the fast.

We interviewed a local orthodox rabbi, Hyim Shafner of Kesher Israel DC. He eloquently phased the Jewish perspective: “We are not being lenient on fasting; we are being strict on guarding your life.” The threat to health does not need to be immediate; if fasting may lead to a weakened condition in context of a preexisting medical condition, it is also reasonable to not fast. He is especially lenient with patients who have eating disorders. Moreover, fasting is not all or nothing. A person may try drinking or eating a small amount of water or food until they feel better, and then resume the fast. He often recommends his congregants consult their physicians, although he has noted that many non-Jewish physicians do not fully appreciate the importance of the fast. The opinion of a physician can influence one’s interpretation of internal bodily sensation. A physician’s reassuring words can reduce anxiety around hunger pangs and feelings of weakness, changing the patient’s feeling of “needing” food into an understanding that it is instead just a strong desire.

The nuances and complexities of Yom Kippur are studied intensely by rabbinic students who go on to serve their communities by answering individual’s questions. Rabbis and physicians are mutually benefited by open communication and collaboration around fasting practices.

Subjective Meaning of the Fast

Fasting is an important cultural and spiritual aspect of Yom Kippur. In the words of Rabbi Jay Michaelson, “Fast days can lead to places that are achingly beautiful: it’s possible to become, albeit temporarily, more loving, more accepting, and more grateful simply by changing the body’s biochemistry for a day.”[1] In Rabbinic Tales of Destruction, Rabbi Belser,2 Georgetown professor of Jewish Studies, discusses the “potent spiritual agency” produced by the intentional abstinence from food. In addition, both public and private fasting are mechanisms of calling for God’s mercy to fend off misfortune.

We set out to collect individual perspectives offered by Jewish members of the Georgetown community, which tended to reinforce and expand on the above sentiments (Table 2).

In total, 81.8% (9/11) of Georgetown University community members whom we interviewed reported fasting on Yom Kippur. Many undergraduate and graduate student interviewees attended Jewish day school or Hebrew school from a young age. This environment, along with family practices, led these students to begin fasting for Yom Kippur upon their bar mitzvah or a few years prior out of curiosity and a desire to participate in a communal practice. For instance, undergraduate Nicole Tepper described fasting as a challenge that her family has undertaken together ever since her mother converted to Judaism for her father, when she and her sister were students at a Jewish school. She recalled that amongst her class, it was considered “cool” to fast once you were of age.

We also found that people were comfortable not fasting if health risks were too great. Physiology professor Aviad Haramati, PhD explained that his elderly mother no longer fasts because of health risks, and that he advised her against fasting because “your relationship to your own body is more important than your relationship to God.” One student described his father opting out of fasting to remain hydrated for his surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. After the physician recommended not fasting prior to surgery, the student’s father decided to forego the fast. However, he felt very disappointed because fasting is part of his Jewish identity. Moshe Levi, MD, reflected that physicians would carry loudspeakers on the streets of Israel, reminding people to refrain from the fast if not in good health, despite the pressure or desire they may feel. Students we interviewed reported not feeling stigmatized if they decided not to fast.

Online accounts of a Yom Kippur without fasting detail the feelings of shame and judgment people experience as they worry about not being “Jewish enough.”[2] Only 33% of students we interviewed reported feeling like there was a strong expectation around fasting. However, these students noted this expectation was highest in Jewish schools and at younger ages, around one’s bar mitzvah. While students acknowledged a stigma around foregoing the fast—and some admitted to judging others themselves—it was agreed that the attitude of judgment has retreated substantially.

One area of dissonance in the interviews related to the communal property of Yom Kippur fasting. Some interviewees found themselves able to observe the fast regardless of their environment, due to their foundational understanding of why they celebrate. Others felt that fasting was made exponentially more difficult by the productivity required in college and graduate school, and the practical inability to attend services or rest while fasting in school. Students and faculty have made headway in establishing a cohesive Jewish community on campus, spreading information on options for holiday celebrations, and providing students a connection with faculty members willing to offer support and home to come together.

Medical Advice on Fasting

Physicians play an important role in the Jewish religion. Their opinions are respected and capable of changing one of the holiest practices on a holy Jewish day. Physicians with Jewish patients should be prepared to answer questions regarding the contraindications to fasting. The primary contraindications to fasting are diseases of metabolism and psychiatric disorders involving restrictive eating practices.

The human body and its metabolic system are excellent at providing sources of energy during prolonged fasts. Through gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis, the liver is able to create metabolic fuel from glycogen, lipids stored in adipose tissue, and amino acids. In fact, fasting has gained public attention in recent years for its health benefits and is currently being studied as a way to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease. A 2019 review noted, “intermittent fasting elicits evolutionarily conserved, adaptive cellular responses that are integrated between and within organs in a manner that improves glucose regulation, increases stress resistance, and suppresses inflammation. During fasting, cells activate pathways that enhance intrinsic defenses against oxidative and metabolic stress and those that remove or repair damaged molecules.”[3] A 2022 randomized clinical trial of 139 patients showed no adverse effects compared with caloric restriction in patients who restricted their eating to an 8-hour period (from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM).[4] Given the evolutionary pressure to develop biological methods to sustain life during periods of food scarcity, these findings make sense.

Rare metabolic diseases arising from mutations in critical proteins can disable the liver’s capacity for gluconeogenesis, thus increasing the risk of hypoglycemia due to fasting. The 6 types of glycogen storage diseases, Von Gierke (I), Pompe (II), Cori (III), Anderson (IV), McArdle (V), and Hers (VI) involve a mutated protein necessary for mobilizing or storing glucose from glycogen stores. Other metabolic disorders, such as urea cycle disorders, are not typically associated with fast-induced hypoglycemia. However, there is a case report of a 14-year-old male adolescent who developed behavioral changes, disorientation, and confusion during his Yom Kippur fast. Blood amino acid analysis showed elevated glutamine level (2552 nmol/mL, normal <756 nmol/mL) and reduced citrulline level (6.6 nmol/mL, normal 12-55 nmol/mL). The patient tested positive for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency.[5] Neoplasms that interact with the metabolic system and can cause hypoglycemia, such as an insulinoma, are contraindications to fasting as well. While these diseases, along with mitochondrial diseases, are very rare, they do represent important contraindications to fasting and should prompt the physician to recommend avoiding the Yom Kippur fast.

Type 1 diabetes requires adjustment of medical care during the Yom Kippur fast. In 2011, Grajower and Zangen3 published endocrinology recommendations for fasting among patients with type 1 diabetes during Yom Kippur. Physicians with such patients should review these guidelines carefully. Briefly, patients with type 1 diabetes should reduce their insulin dosing, monitor their blood glucose frequently, and be prepared with a glucose source to be ingested if either blood glucose level falls below 70 mg/dL or the patient experiences hypoglycemic symptoms. For a patient with well-controlled diabetes, the insulin dose (glargine, levemir, or NPH) should be 33% of normal vs an insulin dose of 50% of normal for a patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Patients with hyperglycemia should have rapid-acting insulin to be taken if blood glucose rises above 250 mg/dL. Absolute contraindications to fasting in patients with type 1 diabetes include blood glucose below 70 mg/dL, definitive symptoms of hypoglycemia, failure to keep blood glucose less than 250 mg/dL, or any signs of hypotension. Grajower and Zangen3 provide a detailed review of management of patients with diabetes during a fast. If the patient has contracted another illness or experienced physical trauma, they should abstain from the fast because this increases the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis. Otherwise, the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis is very low. Finally, because dehydration due to osmotic diuresis is a possibility, the patient should also keep a supply of rehydrating fluids nearby. Overall, without additional contraindications, fasting is safe for patients with type 1 diabetes during Yom Kippur.[6] We found no guidelines for type 2 diabetics. However, similar reasoning applies. Patients should monitor blood glucose frequently, stop if hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) develops, reduce insulin dosing, and keep a glucose rescue nearby. A study of 3441 Orthodox Jewish people with type 2 diabetes between 1999 and 2009 showed that there was no increase in emergency department visits during the 48 hours after commencement of the fast compared with 48 hours before and after the fast.[7]

To our knowledge, few studies have been done specifically examining the effects of Yom Kippur on various health outcomes. An Israeli retrospective cohort study from 2015 showed increased rates of preterm birth in Jewish vs Bedouin populations on Yom Kippur (7.8% vs. 6.8%, P < .001) between 1988 and 2011.[8] However, there are other genetic and cultural factors that may confound these data and explain the increase in preterm birth.

An expanded search including studies on effects of fasting during Ramadan, the Muslim holiday during which the fasts last from sunrise to sundown daily for a month. Studies showed no adverse effects on acute kidney injury (incidence was reduced in fasting cohort), breast milk composition, chronic kidney disease, birth weight, gestational age, or systemic inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.[9]-[10] One study showed reduced birth weights in children born to women who fasted for Ramadan during their first trimester but noted that this was dependent on what food they ate for their breakfast meals. This suggests that pregnant women who fast during Ramadan should seek nutrient-rich meals in the evening.[11]

Finally, there are psychiatric contraindications to the Yom Kippur fast. Restrictive eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, are life-threatening illnesses, and fasting is a potential trigger for recurrence of the disorder. In an essay, To Have an Eating Disorder on Yom Kippur, Resnick4 wrote, “Fasting was an excuse to restrict. It made me feel like I was ‘good.’ It was as if I could prove to the world I did something right. Losing weight was my top priority. I refused to acknowledge the impact it was having on my quality of life. Deep down, I was miserable.” A 2011 meta-analysis of 36 studies on mortality rates in anorexia nervosa concluded that patients aged 20 to 29 years with anorexia nervosa have an 1800% increased risk of dying compared with the general population.[12] Physicians of patients who have a history of such illnesses should speak with their patients candidly about the intention behind fasting and likely counsel them to not fast.

Yom Kippur fasting is a safe activity for most humans, the notable exceptions being for those with metabolic disorders that carry a risk of hypoglycemia and psychiatric conditions such as restrictive eating disorders.

Conclusions

Abstaining from eating and drinking has been an essential part of the Yom Kippur celebration for thousands of years. It continues to be an important aspect for Jewish people in the modern world, and for Jewish people in the community at Georgetown University. As discussed, fasting is important in other cultures and religions as well. Physicians play an important role in advising their patients on the safety of fasting. They should take seriously this responsibility and familiarize themselves with conditions that contraindicate a 25-hour fast.

Sources of Support

None reported.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Loren Bermen, “Fasting on Yom Kippur? Not so fast for me!” Sefaria, https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/264129?lang=bi

Nikki Golomb, “I Can’t Fast On Yom Kippur — And That’s Nothing To Be Ashamed Of,” Forward, September 13, 2018,https://forward.com/scribe/410058/i-cant-fast-on-yom-kippur-and-thats-nothing-to-be-ashamed-of/.

de Cabo, R., & Mattson, M. P. (2019). Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(26), 2541–2551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1905136

Liu, D., Huang, Y., Huang, C., Yang, S., Wei, X., Zhang, P., Guo, D., Lin, J., Xu, B., Li, C., He, H., He, J., Liu, S., Shi, L., Xue, Y., & Zhang, H. (2022). Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. New England Journal of Medicine, 386(16), 1495–1504. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2114833

Marcus, N., Scheuerman, O., Hoffer, V., Zilbershot-Fink, E., Reiter, J., & Garty, B. Z. (n.d.). Stupor in an Adolescent Following Yom Kippur Fast, Due to Late-Onset Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency.

Metzger, M., Lederhendler, L., & Corcos, A. (2015). Blinded Continuous Glucose Monitoring During Yom Kippur Fasting in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes on Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion Therapy. Diabetes Care, 38(3), e34–e35. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-1874

Becker, M., Karpati, T., Valinsky, L., & Heymann, A. (2013). The impact of the Yom Kippur fast on emergency room visits among people with diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 99(1), e12–e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.005

Shalit, N., Shalit, R., & Sheiner, E. (2015). The effect of a 25-hour fast during the Day of Atonement on preterm delivery. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 28(12), 1410–1413. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2014.954998

Chen, Y.-E., Loy, S. L., & Chen, L.-W. (2023). Chrononutrition during Pregnancy and Its Association with Maternal and Offspring Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Ramadan and Non-Ramadan Studies. Nutrients, 15(3), 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030756

Negm, M., Bahaa, A., Farrag, A., Lithy, R. M., Badary, H. A., Essam, M., Kamel, S., Sakr, M., Abd El Aaty, W., Shamkh, M., Basiony, A., Dawoud, I., & Shehab, H. (2022). Effect of Ramadan intermittent fasting on inflammatory markers, disease severity, depression, and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: A prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterology, 22(1), 203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02272-3

Pradella, F., Leimer, B., Fruth, A., Queißer-Wahrendorf, A., & van Ewijk, R. J. (2023). Ramadan during pregnancy and neonatal health—Fasting, dietary composition and sleep patterns. PLOS ONE, 18(2), e0281051. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281051

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality Rates in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating Disorders: A Meta-analysis of 36 Studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74